Editor's note: This article originally appeared in the Spanish language magazine El Budoka. Translated by Santiago Garcia Almaraz Sensei. Read it here: El Budoka

Read the Air

The best martial artists can anticipate their opponent’s next move and defeat them. In Japanese, one way to say “anticipate” is (見越す) or mikosu. Mikosu translates as “to see” (見) and “to exceed” (越す) and thus it implies that anticipation is “to exceed what can be seen.” The word anticipate was coined in the mid 16th century and means “To be aware of (what will happen) and take action in order to be prepared.” In the martial arts, to be able to anticipate is to understand a person’s tendencies and use that knowledge to defeat them.

Anticipation is a form of strategy. It is one way to engage our opponents and defeat them. Sun Tzu once wrote, “Engage people with what they expect; it is what they are able to discern and confirms their projections. It settles them into predictable patterns of response, occupying their minds while you wait for the extraordinary moment — that which they cannot anticipate.”

Anticipation begins with learning to develop one’s eye. In this sense, we are not talking about having sharper vision. To develop one’s eye is to be able to see subtleties and understand them within a certain context. The beginning of developing one’s eye starts with something called minarai keiko (見習い稽古) or “The practice of watching and copying.” The teacher demonstrates and the student carefully watches and copies. This “no teach” method of teaching forces the student to apply themselves or to have self-discipline. Thus, a dedicated student learns to watch so carefully that they are able to see every subtlety of their teacher’s technique, good and bad.

In a 1967 study by researcher Albert Mehrabian, he found that “93% of all communication is non-verbal.” He said, “55% of communication is body language, 38% is the tone of voice, and 7% is the actual words spoken.” Therefore, if we only pay attention to “what” is being said and not “how” it is being said or the body language, then we are apt to misread the words and make a mistake.

In the old days, teachers said very little because it was thought that it was the student’s responsibility to learn. That is why it is said that “the best teacher is the one who is the most unreasonable.” They are unreasonable because they don’t teach us the way we want to be taught. We want to be taught in a way which is the most comfortable for us and reaffirms our egos. The teacher teaches us in a way that brings out the best in us and isn’t necessarily concerned with our comfort. Even a bad teacher can make a good student because, on a certain level, the “worse” or more unreasonable a teacher is, the harder the student has to work. The more unreasonable the teacher, the more it forces the student to “steal” the technique from the teacher. In Japanese, “the practice of stealing the technique” is known as nusumi keiko (盗み稽古).

These types of keiko or teaching methods were also a culling process that was supposed to weed out the students who didn’t have the heart or dedication to follow the art.

Once a student has mastered their kihon-waza (基本技) or “basic techniques,” it is naturally thought that they have developed their eye or ability to see the movement, technique or art. From this mastery is where we develop kan (勘) or “intuition.”

Kan is the basis of being able to anticipate. Intuition is defined as “the ability to understand something immediately, without the need for conscious reasoning.” Without conscious thought makes intuition feel like something spiritual. However, this type of intuition isn’t spiritual but rather learned. It is more of an instinctive feeling that is based upon intelligent repetition. Intelligent repetition means that the movement, technique, or ability improves with every repetition and thus becomes intuitive or done without conscious thought.

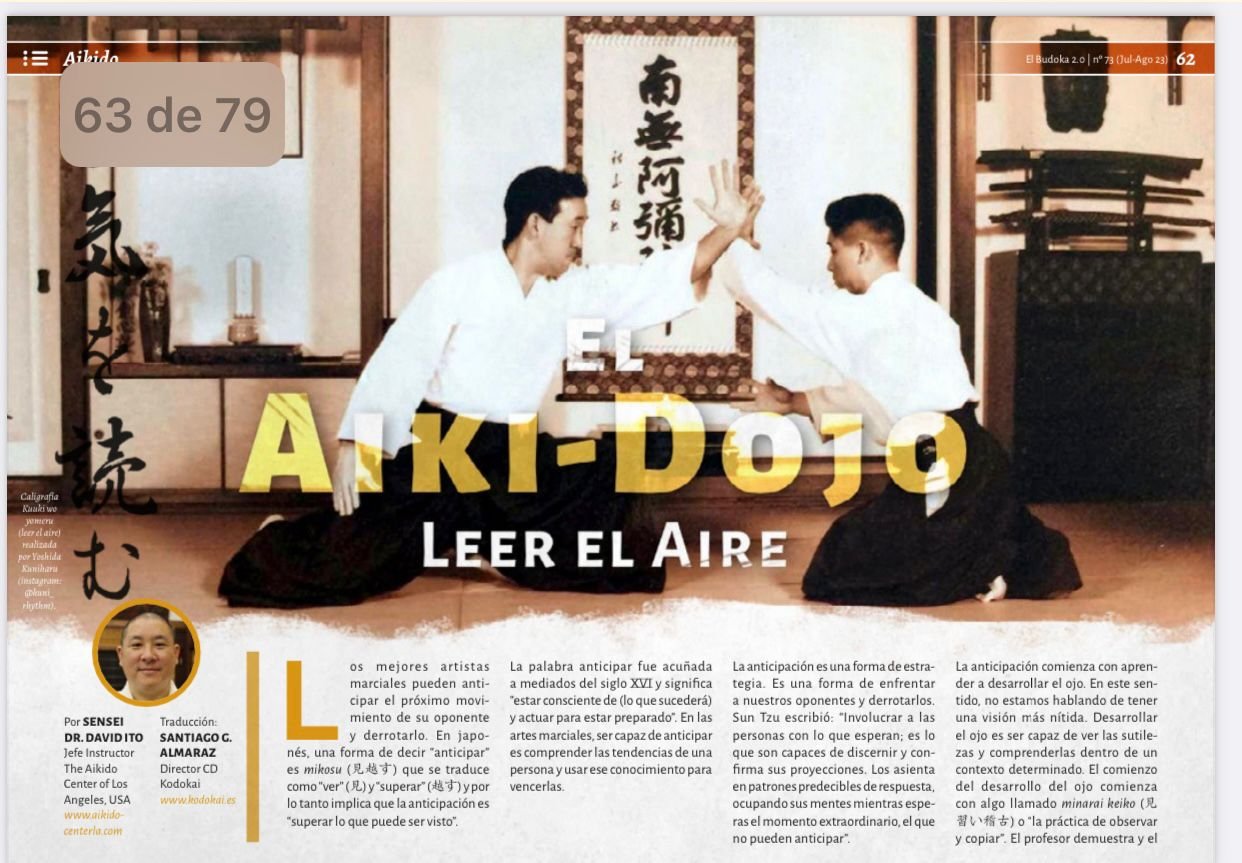

In swordsmanship, a person learns to see the next move based upon their awareness of the situation and an intuition built upon repetition. To the outside looking in, it appears intuitive. In the martial arts, this awareness or intuition based anticipation of our opponent’s next move, is known as kuuki wo yomeru (空氣を読める) or “read the air.” To read the air is a metaphor for being so aware that we can see something that can’t be seen like air. From a martial arts standpoint, a person with training is supposed to be able to see and anticipate their opponent’s next move even if they are trying to conceal it.

There’s a similar concept in chess. The average chess player can supposedly think one to three moves ahead. However, the Norwegian Chess Grandmaster Magnus Carlsen can supposedly see or anticipate 15-20 moves ahead of his opponent. Carlsen’s fastest game was with the Indian Chess Grandmaster Vidit Gujrathi and it took only 6.17 seconds and five moves for Carlsen to offer the Grandmaster a draw.

Learning to read the air is a special type of training that is typically reserved for apprentices who are acting as the teacher or master’s 0tomo (お供) or “attendant.”This training usually happens outside of the dojo. It is the otomo’s job is to see to the needs of the teacher or master. They cook, clean, take their ukemi, teach lower ranking students, and accompany their teachers on errands and travel. If a student or deshi is trained properly or is at a certain level, the master will never have to ask them for anything. The otomo or deshi is supposed to be able to anticipate what the teacher needs before they have to articulate that they need it. To be able to anticipate the needs of the one we are caring for is a demonstration of a very high level of training or ability.

When we face off with our opponents, we are trying to read their movements and at the same time look for any openings to capitalize on. We use our intuitive eye for movement that we learned in minarai keiko and nusumi keiko and apply it to reading the air. With that knowledge, we make it look easy as we handedly defeat our opponents because we know before they know what they are going to do. At this level, we want to get to a level where we can “feel” what is coming next rather than think of what is coming next. This ability to anticipate enables us to make the opponent miss or mikiri (見切り) and then allows us to maneuver and hit them or amashi (余し).

In swordsmanship they say chotan ichimi (長 短 一 身 ) or“strong point, weak point, one body.” This means that every person’s body has both weak and strong points. The best martial artists understand this and apply themselves to be able to see their opponent’s weaknesses and capitalize on them even though they are trying to hide them. That is why the best can read the air and anticipate what’s coming next.

Kuuki wo yomeru calligraphy done by Yoshida Kuniharu Instagram @kuni_rhythm

Read the Spanish version here: El Budoka