From the Aikido Center of Los Angeles’ Aiki Dojo Message - Be Transparent

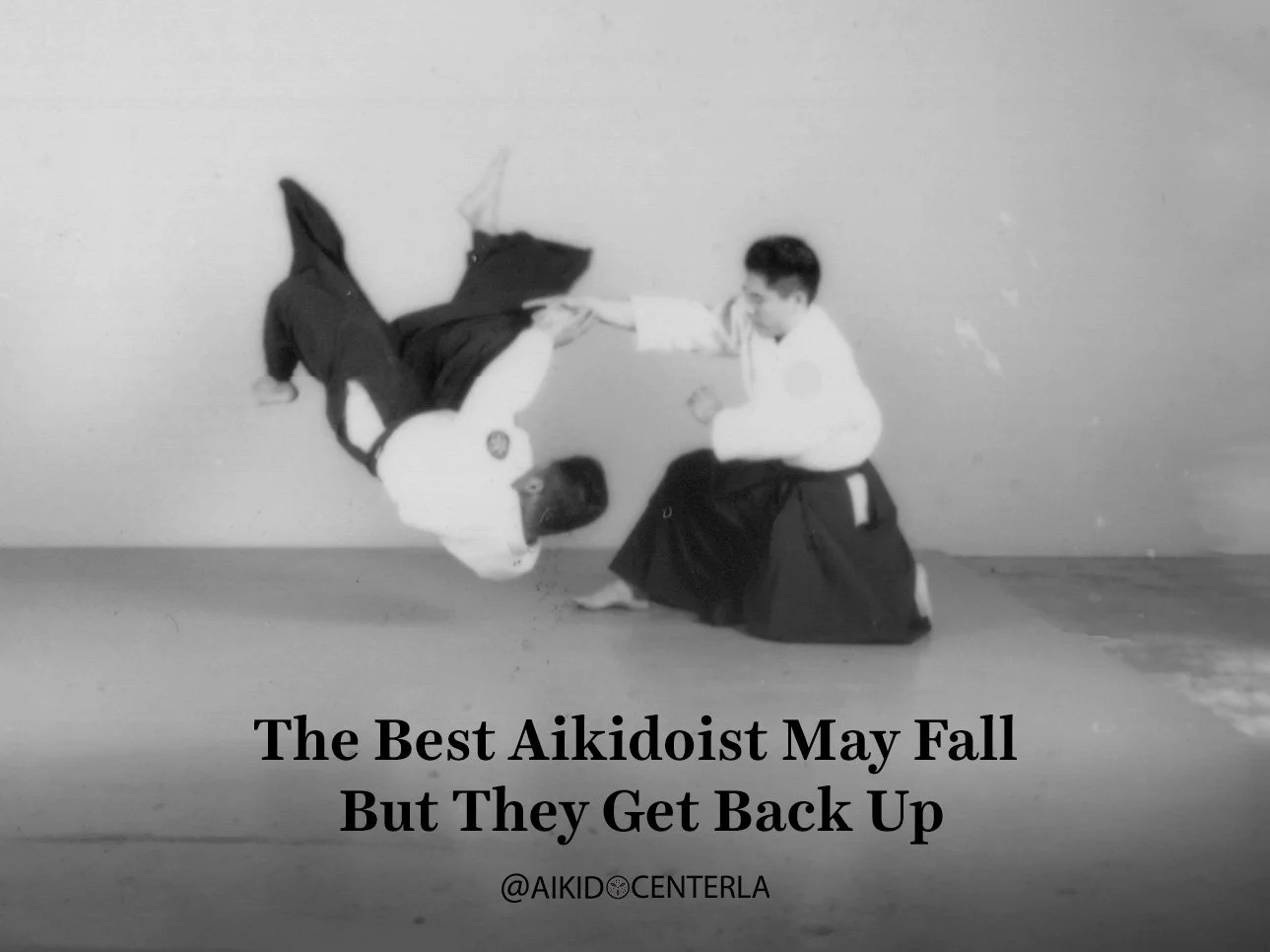

The best Aikidoists strive to be transparent.

Transparent is a metaphor which means that our ability to be calm is so developed that we seem transparent to the anything that is trying to hurt us or disturb us.

The goal of Aikido is not to make ourselves indestructible but rather imperturbable. Indestructible is defined as “not being able to be destroyed.” To be imperturbable means “unable to be upset or excited; calm.” Indestructible is a physical construct and is finite and thus can be torn down. Imperturbable is mental and is infinite and its resiliency, if trained properly, cannot be disturbed, penetrated, or destroyed. In Japanese, the word for “transparent” is sumu (澄む) but another definition is “to become serene or tranquil.”

In the beginning of our training, we don’t know how to breathe properly nor do we know how to move appropriately. This causes us to absorb too much of the energy from our opponent’s attack. In addition to the technique being taught, these are two of the main things that Aikido students should focus on. Students should try to move with the attack even if their feet aren’t moving properly or efficiently. What’s most important is to move without freezing up. Later on, our feet will begin to move with speed and power, and movement will become more efficient.

The same goes for breathing or more importantly not holding our breath. At the moment of being attacked, our stress response causes us to hold our breath. Holding our breath raises our heart rate which activates our sympathetic nervous system aka stress and stress causes us to act inappropriately or inefficiently. First things first, try to notice if we are holding our breath. Gradually over time this awareness will enable us to stop holding our breath and begin to breathe more efficiently and thus we can focus on staying calm. We want get to a place where no matter what happens, we don’t hold our breath or never stop breathing.

These two concepts of movement and breathing combined are what enable us to create this idea of dynamic calm. Dynamic calm is a calmness that is fluid and spontaneous. When we have a calmness that is fluid and spontaneous, we are able to allow things to pass through us as if we were transparent.

In Aikido and in Life, things will happen. Some good, some not so good. Transparency enables us to allow those untoward things to come to us and pass through us without holding on to them. Regardless if it is a strike to the head, a terse word from a co-worker, or a problem at work, being transparent enables us to allow those things to pass through us.

A quote attributed to O’Sensei gives us some direction: “Always keep your mind as bright and clear as the vast sky, the great ocean, and the highest peak, empty of all thoughts. Always keep your body filled with light and heat. Fill yourself with the power of wisdom and enlightenment.” One of the greatest gifts Aikido training can gives us is the ability to remain calm in the face of adversity. The metaphor of being transparent gives us something to imagine or strive for. Nothing good comes from allowing our inner selves to be disturbed, distracted, or unbalanced. That is why the best Aikidoists strive to be transparent.

Today’s goal: When something untoward happens, be transparent.