Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in El Budoka magazine in Spanish. It is kindly translated by Santiago Almaraz Sensei.

I am often asked, “How do we determine which technique we are going to do to our opponent?” The answer is, “We do not.” That is because when a person confronts us, we cannot truly know their intentions, how they will attack, or if they have a weapon. Therefore, how the uke attacks dictates which techniques can be done.

Typically, if an altercation is predetermined, then it is fake. How are we to know how they are going to attack us or what type of weapon they will use. However, that doesn’t mean that we can’t be ready to spontaneously address any attack.

With appropriate training, we should be able to negotiate any attack but that still doesn’t mean that we get to choose. All we can hope for is that we move, maybe not perfectly, but at least to a point that will most likely save our lives.

We can estimate a possible technique to do by being ready. We can be ready in two ways: predetermined or premeditated.

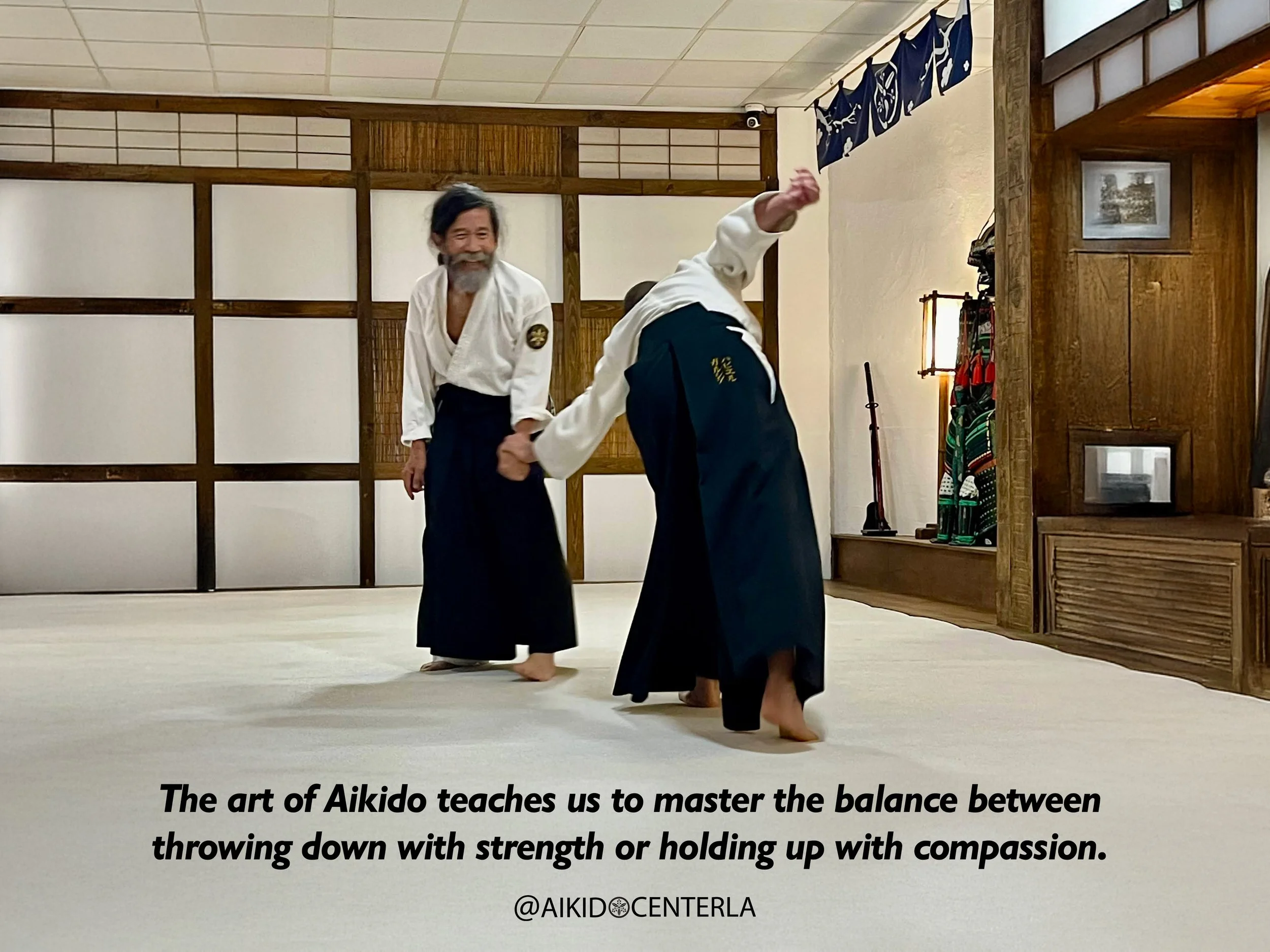

I mentioned that predetermined is fake but this is different if we are using it in the context of training because all martial arts training is based in kata (型) or “predetermined movement.” But what is different is, regardless of the context, it must always be budo. It is budo because budo, even in a training context, requires a sense of honesty and realism. Realism in the sense that our partner is really trying to attack us. In class, it is the uke’s job to bring the level of realism to the encounter. To do this, the uke should attack with sutemi (捨て身) or “total commitment” and the spirit of just a little more. A little more means accentuating elements like speed, strength, or pressure just to name a few. These little things push the nage out of their comfort zone and helps them to grow. Furuya Sensei said, “Always take it to that person’s level and one step further.” That little extra is “budo” in that it brings a sense of honesty and realism to the training and helps them develop resilience and a thicker skin.

Also, the repetition from kata helps form our muscle memory and enables us to create subconscious patterning in our responses to a specific type of attack. From this subconscious place, our bodies move and release the muscle memory in the form of a trained technique in response to how our opponent is attacking us. We could mistake this for getting to choose the technique, but this is subconscious programming and done at a speed higher than conscious thought.

No attack is exactly the same and the attack response might not perfectly fit the attack, but our response could fit a similar line of attack. No matter what style of fighting, all attacks follow the seichuusen (正中線) or “centerline” perspective. This theorizes that there are only nine angles from which to be attacked from: the left side, the right side, cross the body from the top, cross the body from the bottom, top down, bottom up, and straight forward. Everything else is about what implement the attacker is employing to generate carnage or power whether it be a grab, fist, knee, kick or some other sort of weapon. For instance, if a person uses a right cross punch, then they are trying to strike with rotational power on one side and with one angle. Their hips would turn into the punch more than it would for an overhand punch. This is similar to the mechanics of yokomenuchi. Thus, our muscle memory movement moves us in a similar movement pattern in response to the attack. It is not exactly the same, but our movement pattern for yokomenuchi will still enable us to move defensively to dissipate the kinetic energy and not absorb the power from the strike and hopefully enables us to create an offensive movement out of it.

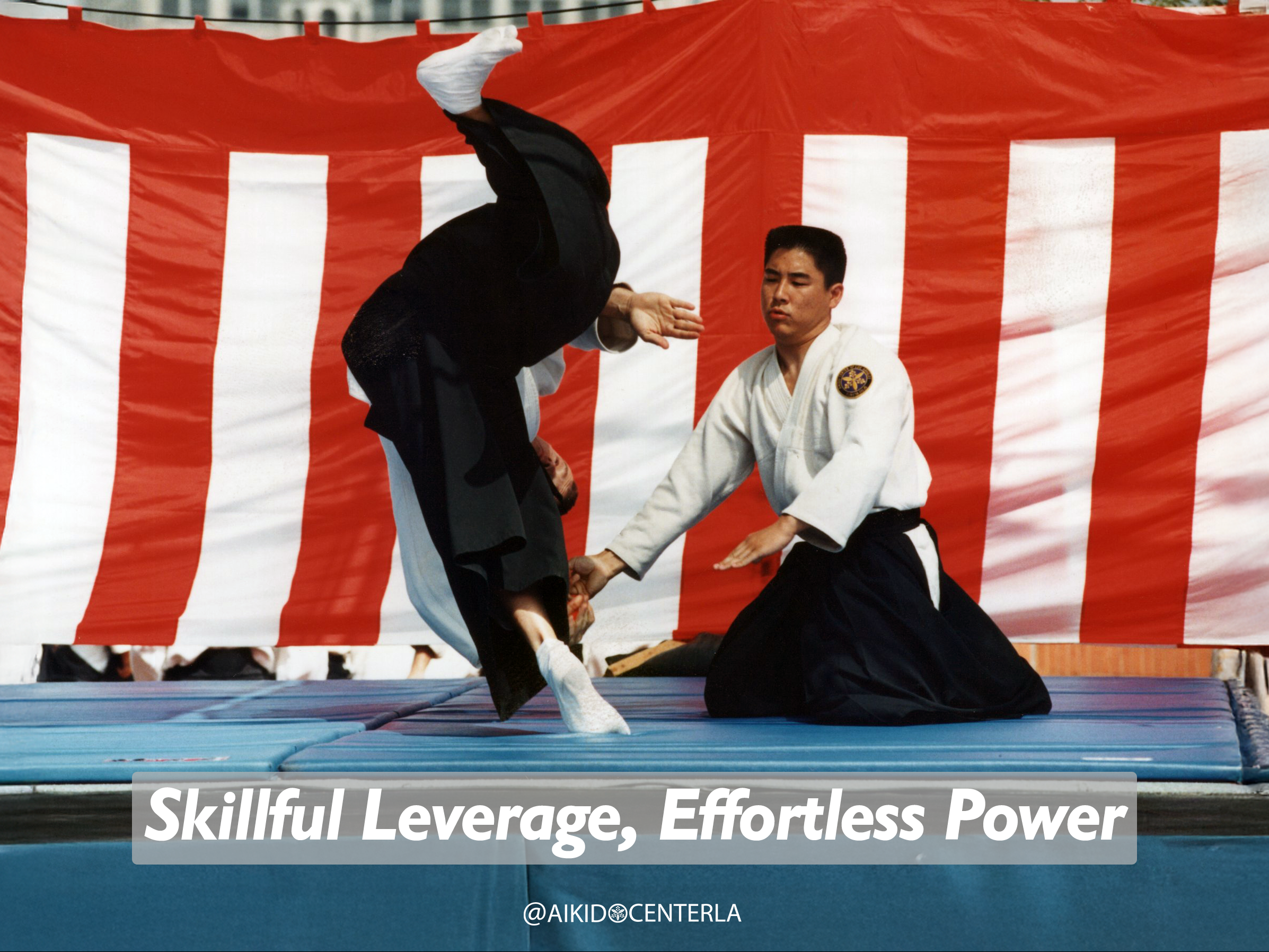

With this understanding, we realize that every specific attack angle has a logical direction of generated power and balance. Generally speaking, human beings can only generate power in one direction at any one moment in time. We cannot be trying to generate linear power while we are also trying to generate rotational power. If we take in consideration a straight punch. It can only be linear and can’t also be making a large curve at the same time. Another example might be how it is very hard to grab someone and also push and twist their arm at the same time. We might be able to generate power in opposite or different directions but the power or physics to do so would cause each of them to be weaker or lack any real strength.

Which technique we could use can also be premeditated or calculated. As we engage our opponent, we should kuuki wo yomu (空氣を読む) or “read the air” and analyzing our opponent’s disposition or movement. Analyzing body language gives us a sense of things like strength, speed, or style of fight training to name just a few. This enables us to load in the programming for dealing with a person with these types of archetypal features. For instance, if a person is engaging us with a kyphotic or hunched over stance, we could surmise that they might be someone trained in some sort of grappling. This understanding forces us to consider the proper spacing, timing, or techniques to utilize. At the same time, we also have to gain an intuitive sense of our adversary’s intention, or inner state of mind. They say the outside reflects the inside, so we look for clues that give away their intention or temperament. For example, that’s why we are told to never look our opponents directly in the eyes because the eyes are the windows to the soul and a good opponent could gain a sense of our disposition and know how to exploit things that we are scared of, anxious about, or lack confidence in. When we find these suki (隙) or “openings” or “weaknesses” in their defense or offense, we make a mental calculation and premeditate a response and choose a technique that we think will have the highest success rate. All this is done in a split second and thus also not a part of conscious thought.

At the peak of training, some people get to the level of shikake waza (仕掛け技) where they “create openings to initiate attack.” Here an attacker might try and capitalize on an opening but find themselves in a trap. This sort of trapping kind of strategy could enable us to dictate the technique. However, if we haven’t truly attained this level, it can be dangerous or hubris to do so because we just set ourselves up to not only to be attacked but also most likely defeated as well.

Martial arts is not mind reading. Therefore, we cannot in good conscience think that we dictate the technique. If we can, most likely, it is fake and fake isn't budo. All we can do is train and hope that the technique springs forth from our muscle memory and subconscious programming. Budo requires honesty and realism and so in all honesty, “No, we don’t get to choose the technique.”