"A warrior uses their sword only when they have no other choice.”

- Quote attributed to Miyamoto Musashi

The best Aikidoists always exercise restraint.

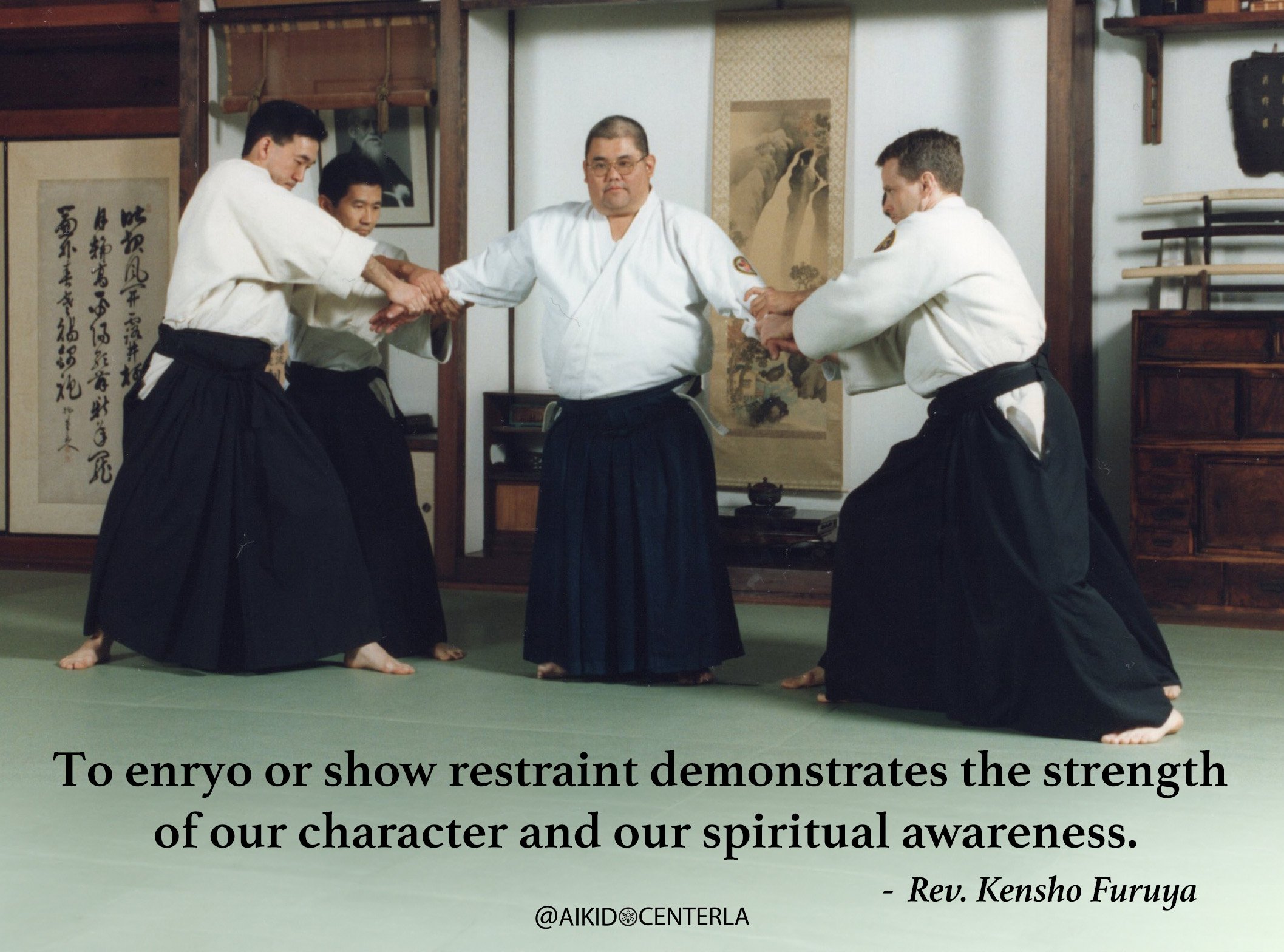

In Japanese the martial arts, an often used proverb is yaiba ni tsukimono wa rei ni suguru (刃に強き者は礼にすぐる) or “The best warriors surpass all others in decorum.” To exercise decorum not only in regular life but on the battlefield requires restraint or discipline. One way to say “restraint” in Japanese is enryo (遠慮). Enryo can also mean “constraint,” “modesty,” or “to hold back” but it is really one of those Japanese words that is difficult to translate. Furuya Sensei once explained, “In Japanese, we use the word enryo which means to be reserved or to hesitate. It also means to be humble and modest. To enryo in a sense is to become closer to the other person. For old fashioned Japanese, it is always good to enryo or show modesty. Today, we are much too pushy and flagrant! The samurai were always to enryo because for them, it showed quiet, hidden strength. To enryo or show restraint demonstrates the strength of our character and our spiritual awareness. It demonstrates our reserved, inner courage - the highest quality of a good student.”

Restraint is about boundaries. We cannot have restraint if we do not know our boundaries and we can’t truly maintain our boundaries without restraint. Restraint is the ability to not only know our boundaries but the ability to exercise them in a healthy and appropriate way. Restraint is the inward discipline applied to our boundaries. Basically, it is the ability to apply only as much of what is absolutely necessary to achieve the optimal result. Thus, as the quote attributed to Musashi states: "A warrior uses their sword only when they have no other choice.”

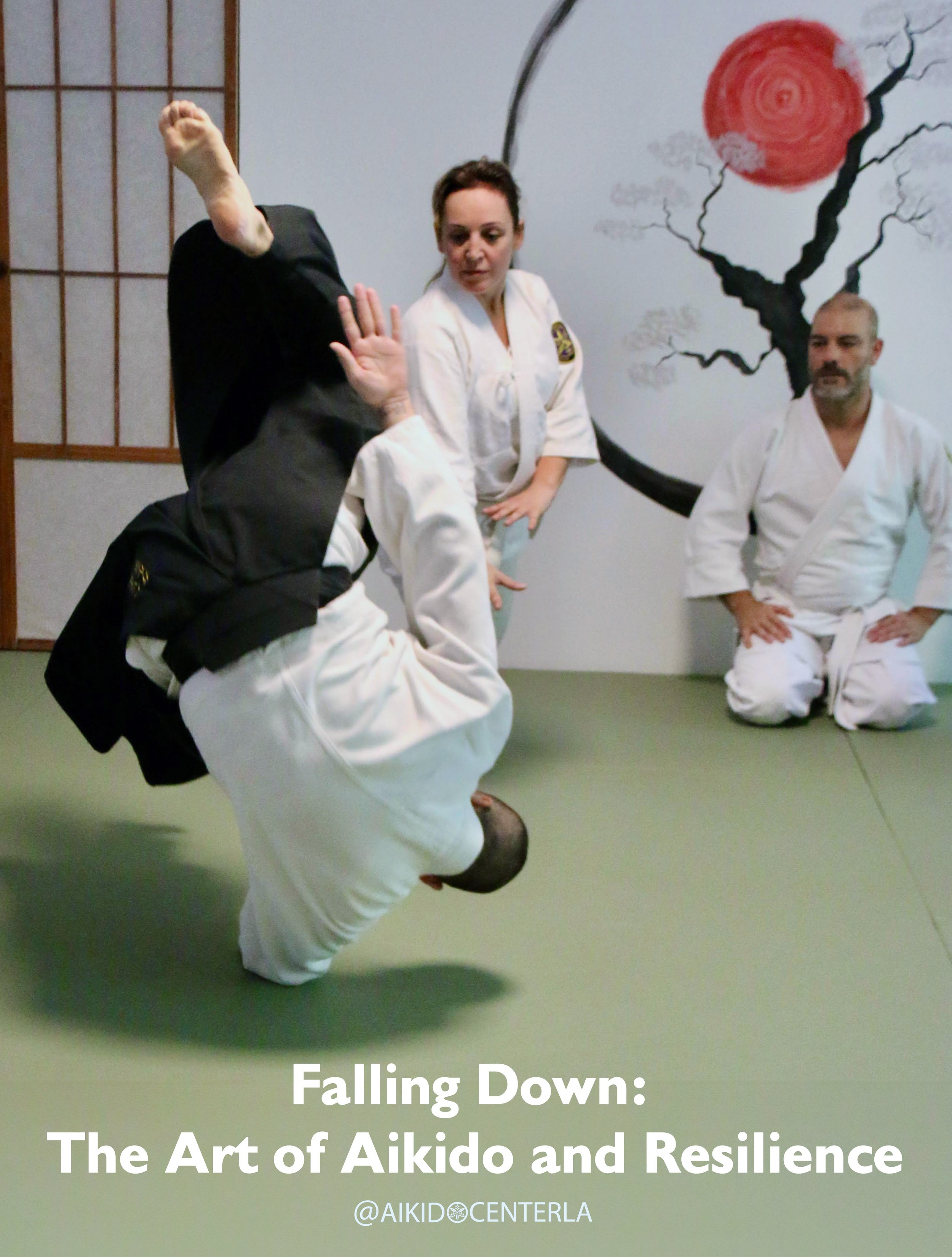

Training teaches us about boundaries and how to exercise restraint. The nage or “the one who throws” tries to push the outer boundaries of what they can do. They want to know exactly what they are capable of achieving. Inwardly, nage’s have to learn how to govern that boundary and exercise restraint within that boundary. If we overstep our boundaries, we could get injured or make a mistake. Also, if we overstep our or other people’s boundaries, then they could get injured as well.

The uke or “the one receiving the technique” is also testing the outward boundary of what they can do physically. Ideally, the better the nage, the more they can help push the uke’s boundaries and the uke in turn is freely giving them their body. The problem is that the nage might not be aware enough to know the limits of the uke’s boundaries. This is where the internal aspect of restraint comes into play. The uke should know their true limits and have the courage to speak up and be assertive when the nage is pushing them too far. Restraint in this sense is not allowing ourselves to be pushed too far outside of our boundaries and pushing the limits of our assertiveness. Typically, that means using our voices before we have to resort to retaliatory violence.

To understand restraint and boundaries, Aikidoists should think of themselves as castles. The Japanese expression that comes to mind is kinjouteppeki (金城鉄壁) which means “invulnerable” or “impenetrable castle walls.” The literal translation of kinjouteppeki is “Gold castle with iron walls.” We are the gold castle which is bordered by iron walls. Walls have two sides. The outer boundary of the wall restrains what can come in and the inner wall restrains what can come out. Therefore, the restraint of our boundaries are protecting us from other people but at the same time they are protecting them from us.

Today’s goal: Know yourself, maintain your boundaries and always exercise restraint.

Watch this video of the Holistic Psychologist explaining the basics of boundaries.