I am sure like most people, as the days, weeks, months and years wane on, we can sometimes lose focus or dedication. I know for myself, I like to read about other people's lives in order to gain a perspective on my own life. I found this interview that Furuya Sensei gave to Budo Videos back in 2004 about his life in Aikido and Zen. Sensei was a pillar of dedication and devotion to his students. I think this interview is worth reading regardless of one's style of martial art. I found it very interesting and inspiring both as an Aikido student and teacher too.

I am sure like most people, as the days, weeks, months and years wane on, we can sometimes lose focus or dedication. I know for myself, I like to read about other people's lives in order to gain a perspective on my own life. I found this interview that Furuya Sensei gave to Budo Videos back in 2004 about his life in Aikido and Zen. Sensei was a pillar of dedication and devotion to his students. I think this interview is worth reading regardless of one's style of martial art. I found it very interesting and inspiring both as an Aikido student and teacher too.

This interview appears on Budovideos.com

Kensho Furuya Interview July, 2004

Rev. Kensho Furuya, Aikikai 6th dan, is the chief instructor of the Aikido Center of Los Angeles and has just celebrated his dojo's 30th anniversary. In this interview he speaks about his training with the late Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba at the Aikido World Headquarters Hombu Dojo in 1969. Rev. Furuya teaches both Aikido and Iaido full time and is also ordained as a Zen priest.

Budovideos.com conducted this interview in July of 2004.

BV: How long have you been involved with Aikido and Iaido?

I remember that I started Kendo when I was around 8 years old and Aikido sometime soon after when I was about 10 years old or so. I do remember that I bought my first real sword at 10 years old in order to practice Iaido more intensely at the time. I was very enthusiastic at that early age much to the chagrin of my parents. I have been doing martial arts all of my life, maybe due to the influence of my grandparents very early on. My grandfather first introduced me to Kendo through his old friend from the old country. He was a Kendo 9th Dan and master of Itto Ryu and Muso Shinden Ryu Iaido. Although my parents wanted me to be very much "all-American," I was drawn more to my grandparents influence who were very proud of their samurai heritage and lineage and loved to tell me all about Japanese culture. I think this cultivated my strong love for martial arts. I really don't know but I do remember when I first stepped onto the Aikido mats, I was very young nervous and shy - but I felt deep down inside at that moment that this is what i wanted to do for my whole life.

I remember meeting the late 2nd Doshu, Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei and Akira Tohei Sensei who was his uke at the time, on their first visit to the United States in 1962. I traveled to Hombu in 1969 to train under 2nd Doshu. Now, it is about 47 years now. I just celebrated the 30th anniversary of my dojo this last April which was established in 1974.

BV: What initially attracted you to these arts?

I can't remember what really attracted me - I have always been drawn to Aikido my entire life, as well as Kendo and Iaido, and cannot remember any time when I was not practicing Aikido and I cannot remember ever thinking of doing anything else in my life. Although I have had the opportunity to study many other martial arts - all has been to enhance my own Aikido practice.

BV: For students that don't practice the art, what would you say are the main benefits to practicing Aikido?

There are always the usual things to say - Aikido is good physical discipline, a great martial art and there is a deep spiritual background as well. Beyond this, I must honestly say that I think Aikido has had its influence in every aspect of my life. I should say that there is nothing better than a life in Aikido - with both all the tears and disappointments and moments of great happiness that it brings - I cannot think of having a more fulfilling and meaningful life outside of Aikido. I also felt I had an inner calling to the priesthood - probably from reading too much the great warriors and swordsmen of the past who devoted their lives to their art. We were so desperate for knowledge in those early days and pursued anything that we thought would help our Aikido practice. I really thought that by entering strongly into Zen, I could understand martial arts more deeply and that this would enhance my Aikido further. It is really hard for me to say, it is really hard to talk about myself like this so personally. . . . .

It was my meeting with the late Aikido great, Kisaburo Ohsawa Sensei, at Hombu that helped me to find the right path in this pursuit of both Aikido and Zen. Ohsawa Sensei was also a student of Sawaki Kodo Roshi who I was later to find out - also happened to be the teacher of my Zen master. He never mentioned a word to me about pursuing Zen but somehow he let me know everything I needed to know. I remember I was with one of the top teachers of Aikido at Hombu observing Ohsawa Sensei's wonderful Aikido demonstration. I turned to him and asked, "How can Ohsawa Sensei move like that?" This teacher turned to me and simply said with a shrug of his shoulders, "Well after all - Ohsawa Sensei is enlightened!" Along with Doshu's many personal instructions to me, this was the great turning point in my life.

Later, I finally met my Zen teacher, the Bishop Kenko Yamashita, who was also a Kendo 5th Dan under Nakayama Hakudo Sensei whose lineage I was also following. It was in 1988, almost 20 years later, that I was ordained as a Zen monk in the Soto-shu lineage. Many strange events such as this all connected themselves in my life through Aikido. Still, I do not understand such mysterious relationships and connections and how they occur and just happen as they do to me - maybe it is just karma through Aikido. I cannot recall all of the other things which have happened to me because of Aikido. I think it is hard to say how much of my inner strength came from my training in Zen or from Aikido and my pursuit to understand it. In many, many ways, Aikido can be so fulfilling - it is almost trivial for me to try to put all of this into words and only use this one tiny episode about my Aikido and Zen to illustrate how such wonderful and mysterious things open up to you in your training and in this path of discovery. I think it is up to each individual to enter this Aikido path and achieve his own understanding and enlightenment. The first step is to step onto the mat for practice and all at once a whole new world will open up to you. I truly believe this.

BV: How do Zen and Iaido training complement your Aikido?

As much as I have a bad habit to speak too much about Zen, in practice, I an not trying to promulgate Zen or solicit practitioners to Zen. In the Dojo, those interested in Zen are recommended to attend Zen meditation classes at my temple under more experience priests and the Iaido class in the Dojo is separate from the Aikido. As much as possible I keep each class separate without mix and matching the two. Iaido is taught as pure Iaido and Aikido is taught as pure Aikido. For Zen, they must go to the temple and seek out pure Zen.

As for myself, I think within the students too, it will all come together somehow naturally and with their own understanding and enlightenment. The teacher must plant the seed by teaching the student with a strong emphasis on the fundamentals but it is up to the student himself how he himself grows, matures and in what direction he takes his art. In practice, the first step is the most important, however, the first step is to master the correct fundamentals, so the teacher is very important in this respect. It is important for the teacher to keep in mind his role in the student's upbringing.

My interest in Zen came from my own inner feelings of a "calling" to the religious life ever since as was a small child. I do not understand this myself because there was not the strong emphasis in religion in my upbringing. I think my interest in Zen became very strong with my meeting with the late Kisaburo Ohsawa Sensei at Hombu and finally meeting my Zen master, the late Bishop Kenko Yamashita. Iaido, as I have mentioned before, is something I started when I was just a small child so it has been with me all my life as well as my Aikido practice.

Zen and Iaido is very obviously related, philosophically and historically. The relationship between Aikido and Zen is more distant and only in this respect that Aikido's roots are in traditional Japanese Budo.

In my own mind, Zen, Iaido and Aikido are very compatible and for my own personal training, I myself do not see how one can do without the other. However, in class, I do not particularly try to emphasize this point and try to give purity of the arts to my students.

In Aikido, as everyone knows, it is important for the movement to flow and create a strong connection with the opponent's movement. However, in actual practice, it is easy to get stuck or jam one's self against the opponent's strong attack. Sometimes, we miss the timing, sometimes our spacing is off, or we get intimidated by the opponent's power and this flowing process stops or gets blocked. This continuous, flowing movement in Aikido seems very similar, in my own mind, the concept of "muju-shin" in Zen - or the idea of the "non-residing" mind. In Zen, the idea is to allow the mind to flow freely without residing anywhere or to get stuck or obsessed at any one point. This Zen idea of a free moving mind which never gets stuck on anything seems quite similar to me with Aikido's idea for flowing movement in which we can connect or blend with the opponent's attack. As an example, in shomenuchi irimi-nage, it is easy to get stuck against the strong overhead attack of the opponent. We often get stuck against his arm and this prevents us from moving in (irimi) and completing the technique. If we think in terms of Zen, in this case, the idea is not to get "taken in" by the opponent's attack or strength, but allow our minds' to flow freely without getting "stuck" anywhere. In another case such as morote-dori kokyu-ho, we are often get stuck against the two-handed grip of the opponent against our own arm and it is hard to move if he is very strong. Many times we are not stuck or stopped by his strength, we are stuck on the "idea" of this strength or we are intimidated by his attack. The idea, in my view, to create this flow of movement, is to refine the mind of not getting stuck anywhere as taught in Zen.

These are simple examples of how Zen ideas can be applied into practice. In addition, Zen has a strong precept against killing and violence - the idea that all living, sentient beings are enlightened Buddhas cultivates a strong sense of the inner worth of each individual and in this I see a great connection to Aikido's idea that we are all "one family of man" as O'Sensei often spoke about. Finally, I see the peaceful meditative state which Zen cultivates in sitting compatible with Aikido's mental state of always being well centered and balanced, yet maintaining the ability of moving freely and without inhibition or jamming one's self.

In Aikido, I believe there is a strong sense of "form" (technique) but this idea is very subtle and sophisticated in outward appearance. Actuality Aikido is the "form of no-form." In Iaido, the form is very obvious and Iaido teaches how correct form and technique generates proper application of power. In addition, Iaido, like Aikido, is strongly based in timing and spacing, ma-ai, rather than strength and collision power. In this, I feel that Iaido and Aikido are very similar in spirit, although quite different in outward appearance and practice.

These are just my personal views through my years of study and practice in these arts. I don't know if they make sense to others, but I find these arts all help me to do my job of teaching my students and encourage me to continue to refine my understanding in practice.

BV: Thank you for sharing your ideas on training with us. I'd like to ask you now about the various levels of Aikido training. We all know that the basics are very important but how do you teach your students to go beyond the basics?

My primary concern with my students is that they get a good, solid foundation in the basics of Aikido - not anything more than this really - I am not such a great teacher to teach them anything fancy or mysterious. I think teaching them the fundamentals is the most important duty to my students. Like a small seedling, it needs help to be planted in the right soil, cared for, keeping the weeds away, etc., watered and well nourished until a strong, healthy plant begins to sprout. Once the young plant has a good, healthy beginning, it can grow in its own direction depending on how it wants to capture the light of the sun, according to its own nature. Once my students get a good foundation in the basics, both in the physical technique and in the proper understanding of the spirit of Aikido, they will continue to mature in their own way according to their own nature and the unique circumstances and experiences of their own lives. I am just the farmer who plants the seed and gives it a little water and occasionally keeps some of the weeds away.

In martial arts, there is an instruction of the "rudder in the waves." The rudder steers the boat and keeps it from tipping over, but it constantly needs a slight pressure to the left and to the right according to the currents to keep it in proper balance and on its true course. It is up to the student to develop this sense in his training but it is also the lifelong task of the teacher to help his student keep this "rudder" of his practice and his life on true course as well. Although growth is much according to one's own nature, there is also a consideration of "mindfulness" - it is not all random and willful impulse but there is this continual "awareness" as we go along - just as one must constantly keep his hand and eye on the rudder to keep the boat in equilibrium and on true course.

On a more down-to-earth level, once students do well and show good skill, I try to give them the opportunity and experience to teach other students. They start with helping out in the children's class because this is the hardest skill to develop. Young kids are very perceptive, open and honest so it is very necessary for the new teacher to be equally forthright and open. If he doesn't know what he is doing, the kids will sense it immediately. Adults are more forgiving in this respect, I think. I believe in my own training, that teaching is giving, not receiving. There is really no authority or prize or prestige, - just the hard, endless and devoted work of getting the students to practice Aikido properly.

In traditional Japanese arts, in respect to the teacher, there is the idea of Bosatsu-gyo. This means the "training" of a Bodhisattva or "near-Buddha" - although a rather Buddhist idea, it has filtered down into and become vitally characteristic of many areas of the traditional Japanese arts. The "near-Buddha" is one who about to enter the final stage of enlightenment but takes a vow to stay behind until all other sentient beings in the world are saved before himself. This is called Bosatsu-gyo or Buddha-training. In my own thinking, this seems to apply very well to Aikido. A teacher is there for his students, often the rewards are very small and many times there is only disappointment and frustration, but, all the same, the teacher is there for his students and puts his students ahead of his own welfare, more often than not in real practice. I am very concerned about their welfare and like to see my students, as they advance in Aikido, understand and appreciate how Aikido can bring fulfillment and happiness into their own lives. Maybe this is the only reward in teaching. . . . It is a lesson which I hope my students learn and pass on to their students.

To advance in Aikido beyond the basics, does not simply mean to be stronger in technique or develop one's authority, prestige or popularity but to find one's own self which will lead himself and all others around him, at the same time, towards a fulfilling life. I say, "all others around him" because I do not think one can achieve happiness all by himself. I teach my students as they advance that happiness must be shared by all - we are all happy together, not one person is happy all by himself. In the dojo, all practice and advance together, not one person only thinks of himself but must continually see to the well-being of all others around himself. In the dojo, it is often the hardest lesson to learn to get along with each and work together in harmony.

Finally, in addition to what personal development a student achieves in his training, I would always hope that they will help to develop Aikido and maybe help in the task of running the dojo and maintaining a high level of practice and instruction. Nowadays, I find that many of my seniors are becoming fine teachers - I sometimes think that they are much better than me. I am too much of the old-school and my methods are old-fashioned and out-dated. I see my students with younger and fresher outlooks on life and therefore can convey themselves much more easily to the newer students. . . I like this very much.

In teaching at a higher level, I would hope my students would begin to understand to two essential aspects to developing into a fine Aikidoist and martial artist. First is the "free mind" - this is not the mind which is obsessed with personal agendas or self-centeredness. This is the mind which can move freely without inhibition and attachment in the most natural way. A mind which does not cling to any one idea but can be open and honest in all aspects of their lives. I often see students get stuck on an idea or notion and then become blind to all other suggestions. This obsessive attachment is not good in encountering the opponent or in dealing with one's own practice on the mats.

The second is the "caring mind. " The mind which is thoughtful and caring of others and shows compassion to others, not only in practice on the mats but in their lives as well. I think we all like to think of ourselves as caring people but often, without being aware of it ourselves, we can become thoughtless. A caring mind notices everything and such caring can only come from a mind which is totally aware and in the moment. Especially in Aikido, I feel this "caring" mind to be an ideal we should all strive for.

Rev. Kensho Furuya's Sensei's dojo is in Los Angeles.

BV: As far as you see it, what stages does the typical Aikido practitioner go through?

In traditional martial arts, there are three stages called Shu, Ha, Ri. "Shu" means "Protection" and refers to the initial stage of training where he must learn all of the rules and master all of the techniques. It is often like a chick still within the hard confines of the eggshell. "Ha" means "breaking" and it is the next stage where the little chick begins to peck its way or break out of the shell. At this stage, the student has mastered the fundamentals and begins to broaden the scope of his training and knowledge. It does not mean to break the rules or disregard them, it really means to expand and broaden them beyond the initial stage of hard-fast rules. The third stage is "Ri" which means "Separation," like the little chick finally freeing itself from the shell. This does not mean that the student flies away from the nest, it means that he can go beyond mere rules and regulations, having mastered them and now transcending them as something which is now an integral part of his life and life perspective.

In addition to this, I think, as the Aikido student matures, he needs to ask himself many serious questions and begin to think how to apply these Aikido principles into his own life in a reasonable way. As an example, what does it mean "not to fight?" We think we understand this intellectually and by our reason, but in real life, we fight continually with each other every day. What does it mean to be centered and balanced? It is not simply a way to be strong in throwing or pinning someone to the ground, I think it goes beyond this point to where we are centered and balanced in all aspects of our lives in facing all emergencies and encounters that life offers us. I think that when we hear terms like "harmony," "love," "blending," "ki" we immediately think that we understand what such words means. However, our ideas are often in contrast to the "reality" of life and the moment to moment situations we encounter each day in our lives. When we become quiet and think about these ideas with a great deal of seriousness, we find, I think, that we really do not understand them at all. Daily practice is always the constant refinement and deepening of this understanding.

Finally, in O'Sensei's teaching there is this deep, almost divine, reverence for life - how do we understand this for ourselves and bring it into our own lives? I think part of the advancement of my students is to meet, think about, practice and begin to resolve such matters for themselves in their own lives and in their own thinking. This is one of the meanings of training throughout one's life.

BV: Your 9 part video series has just been released on DVD. How much of your Aikido curriculum do you show in these videos?

When I was asked to do this video series, it was repeatedly emphasized that they wanted an "instructional" video and not a "demonstration" video. In much of these videos, the techniques are demonstrated much in the way, almost to the letter, as I teach my regular classes. In addition, they asked for a video series which people could watch and learn from. In the videos, many of the techniques are executed repeatedly and common pitfalls and errors are explained as well as hints to improve one's technique. I also included short talks to help and encourage the student in his practice, just as I do in class. Most of the areas covered in this video series is what I think any beginning student of Aikido should know as a good foundation for his practice. In addition to these nine volumes, there was planned for another three hours of videos to cover advanced techniques and bokken and jo beyond the basic introduction in the present set. Unfortunately, my busy schedule never allowed this.

I have received a great deal of compliments from all over the world and after many years, the publisher reports that it is still doing very well. There is really nothing fancy in the videos but I think it does cover many of the basic aspects of Hombu Aikido. In many of the explanations and presentations of the techniques, I explain them just as they were explained to me by my own teachers. The late Sadateru Arikawa Sensei of Hombu Dojo viewed my tapes when they first came out and I was surprised that he was so complimentary to me. He has always been an excellent, but stern critic and I have always looked up to him with great respect and awe.

Over the years, much as I teach in my dojo is still the same as I teach in the videos. As I say, much of the videos contain all of the Aikido fundamentals and these do not change so much. Nowadays, if there is any change at all, I like to emphasize more connecting the movements and techniques together. I find that students today unconsciously view Aikido technique as a kind of leisure exercise or solely from the standpoint of movement or exercise. I often think that we do not emphasize Aikido as a viable, extremely effective martial art. In other words, i see that we are gradually losing this awareness of Aikido. In this sense, we lose our sense of ma-ai, spacing and timing. In practice, we allow the opponent or partner to move in too close into our space, essentially making us vulnerable and open to counter attacks. Because many practice with a weak or uncommitted attack in normal practice, we lose our sense of timing. Against a weak attack, for example, we may be free to move as we like because there is no threat or anything really to collide with. If the attack by the partner is strong and committed and focused on the target of the attack, then we must move more critically with a high sense of timing and spacing - or we collide or get jammed. This type of training really needs to be under the supervision of a competent instructor so it is not emphasized strongly in the videos. Ultimately, we can only develop good technique against a strong, committed attack. Practice with weak attacks which do not have any energy or not committed to the target, is often the root of many bad habits and with losing our sense of critical timing and spacing, the essence of all Aikido technique.

The publishers informed me that out of an inventory of over 350 videos series which they have produced over the years, this Aikido series was their first choice to convert into DVD. I was very happy to hear this. I was told that video become "stale" after three to four years but this Art of Aikido still seems to be doing very well. I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone for all of the wonderful letters and emails regarding the video series and I am glad that it is helping many students around the world in their practice.

In the new DVD series, they are added an extensive index and many more new chapter headings so it is easy to find a specific technique just by clicking on the heading. I like this new innovation very much and I think it makes the DVD series much more convenient to use than the original videos.

BV: What are you working on in terms of your personal training?

Personal training? The continual job of trying to make myself a better person and teacher - an often hopeless, discouraging and sometimes despairing job! Ha-ha!

At the moment and for some years now, I have working hard to develop my senior students as instructors and gradually supervising their training as future teachers. We now have about 18 branch dojos all over the world and this has increased my workload and responsibilities tremendously. I still continue to write a great deal, publishing a monthly newsletter and answering correspondence each day from all over the world. I have several books in the works which I would like to finally finish if I can squeeze in the time. One is an Aikido technique book for which we have over 5,500 photos of Aikido techniques which need to be arranged and captioned.

I have lost much of the ambitions I had when I was younger, I suppose, and this has caused me to think more of the development and advancement of my students than for myself. Personally, I am trying to understand Aikido as it pervades one's whole life from one moment to the next in my daily life. Although I left the temple when my teacher passed away, I still try to lead a priestly life and prefer a quiet, solitary life. Recently, however, three of my young students have just had three new daughters, two students have just had two granddaughters - all within the last several months, so I have become quite envious of them and rather long for the "family" life which I gave up in my younger days in order to pursue Aikido as I wanted

As we get older, I think, we move a little slower and our bones creak a little more, I try to see Aikido more from the standpoint of a sharper sense of timing, than from the speed and strength of my youth - many years ago. Also, as I mentioned elsewhere in this interview, I am interested to resolve and understand the principles of Aikido in my life and how they work in how we think and act.

At the same time, I think students today are busier with their lives and have less time and energy to devote to their training. i am studying how to transmit Aikido to today's students without sacrificing its vital essence as a martial arts. i often get the impression that Aikido is moving away from its original mandate as a martial art.

In addition, in today's rapidly changing world, I see a lot of Aikido's ideals changing and, to some degree, getting lost in our highly complex, complicated world of today and despite the fact the it is not the popular trend, and so in many ways, I want to keep Aikido as much as it was in the early days of my training for my students.

Nowadays, I find myself introducing elements from my personal style of Aikido, rather than adhering strictly to very orthodox Aikido technique as I normally do for my students. In Aikido sword training, I have gone back to very basic sword fundamentals and have strongly emphasized more attention to proper grip and footwork and a much stronger cut more like the cut of a live blade. With a stronger cut more aimed at making contact, I have noticed that the timing and spacing of the techniques are naturally changed to more effectively get out of the way of an unstoppable cut.

Over the years, the general public is more educated in martial arts than thirty years ago. In the early days, martial arts was an exotic, mysterious thing from the inscrutable East - we knew a little of Judo and have seen Karate but Kung Fu was still a kind of mystery but all of this has changed and there are all commonplace terms which most people are quit familiar with. In this respect, in my intermediate and advanced classes, we practice against a wider range of tsuki, other than the normal "tsuki" we use in Aikido training. It is a very interesting training to execute Aikido techniques against upper cuts, hooks, jabs, double and triple punch combinations and counters against multiple strike and punch combinations. This has opened up a wide area of study for me in my own practice.

BV: Sensei, thank you for sharing your time, experience, and thoughts with us today!

Source: http://www.budovideos.com/pages/kensho-furuya-interview-july-2004

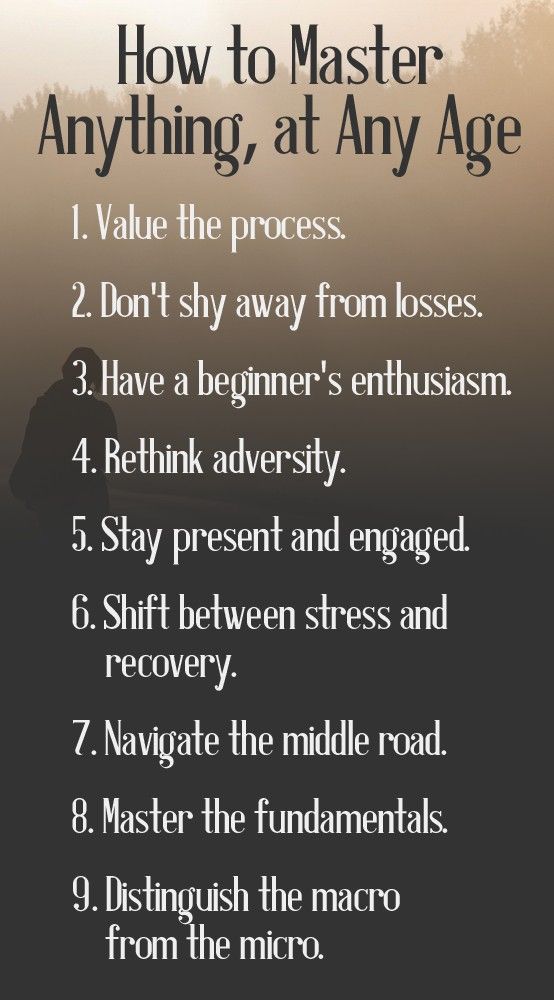

How discriminating is your eye? The mark of good student is not in what they can do, but what they can see. What one sees is a function of "how" they see things or their perspective. To be a good student requires that one's perspective be open and willing to see things beyond what is being shown. With the picture above, one can see just how discriminating their eye has become in both good and bad ways.

How discriminating is your eye? The mark of good student is not in what they can do, but what they can see. What one sees is a function of "how" they see things or their perspective. To be a good student requires that one's perspective be open and willing to see things beyond what is being shown. With the picture above, one can see just how discriminating their eye has become in both good and bad ways.