The best Aikidoists know when to stop resisting.

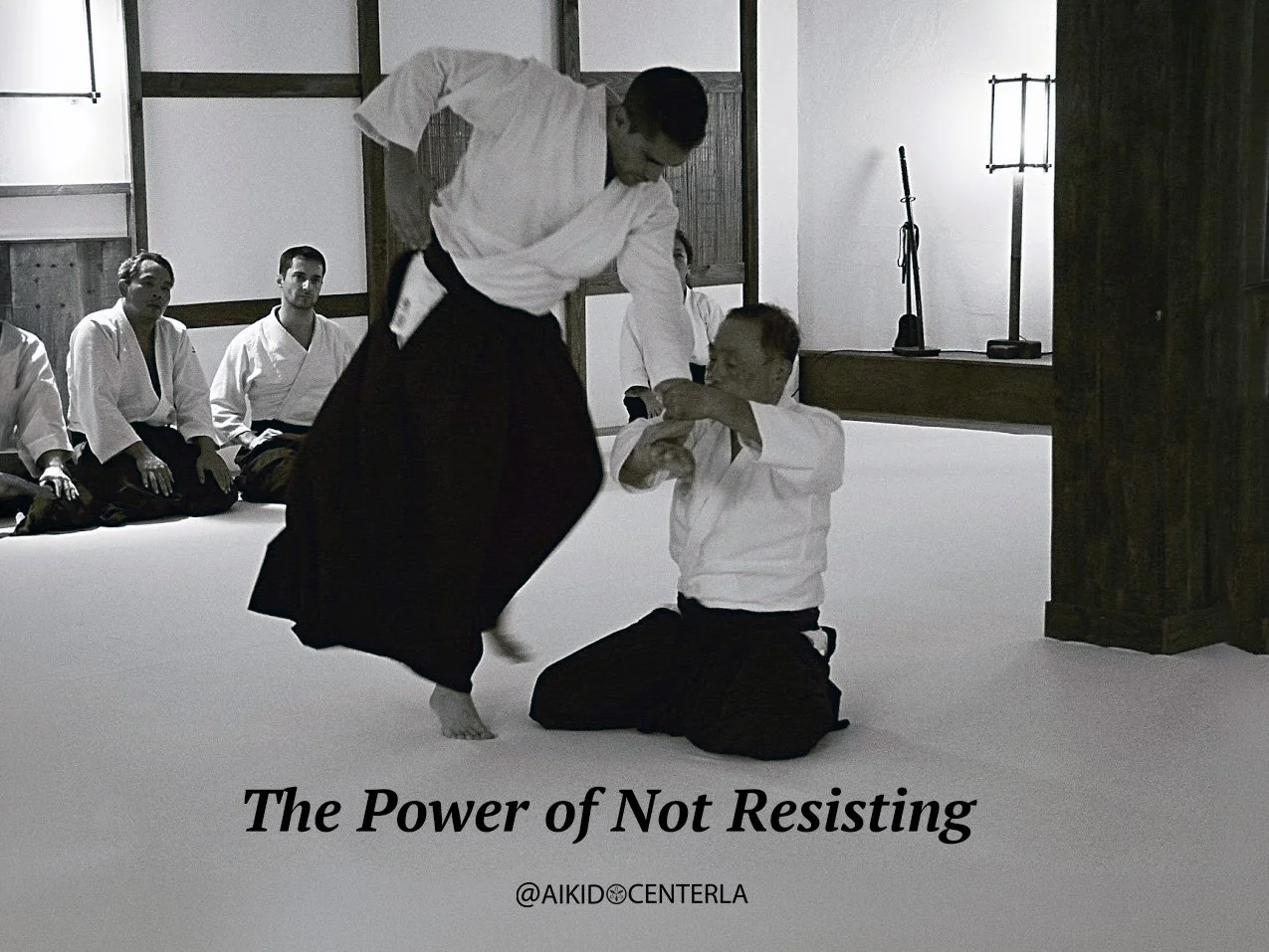

Within every technique, there is a moment where we know that our partner’s balance is broken. It is a weird lightness, but lightness is not quite the right word because it implies that it has something to do with weight. Maybe ukiyo (浮世) or “floating” is a better word but that too can gives us this weird poeticness which can also be misconstrued.

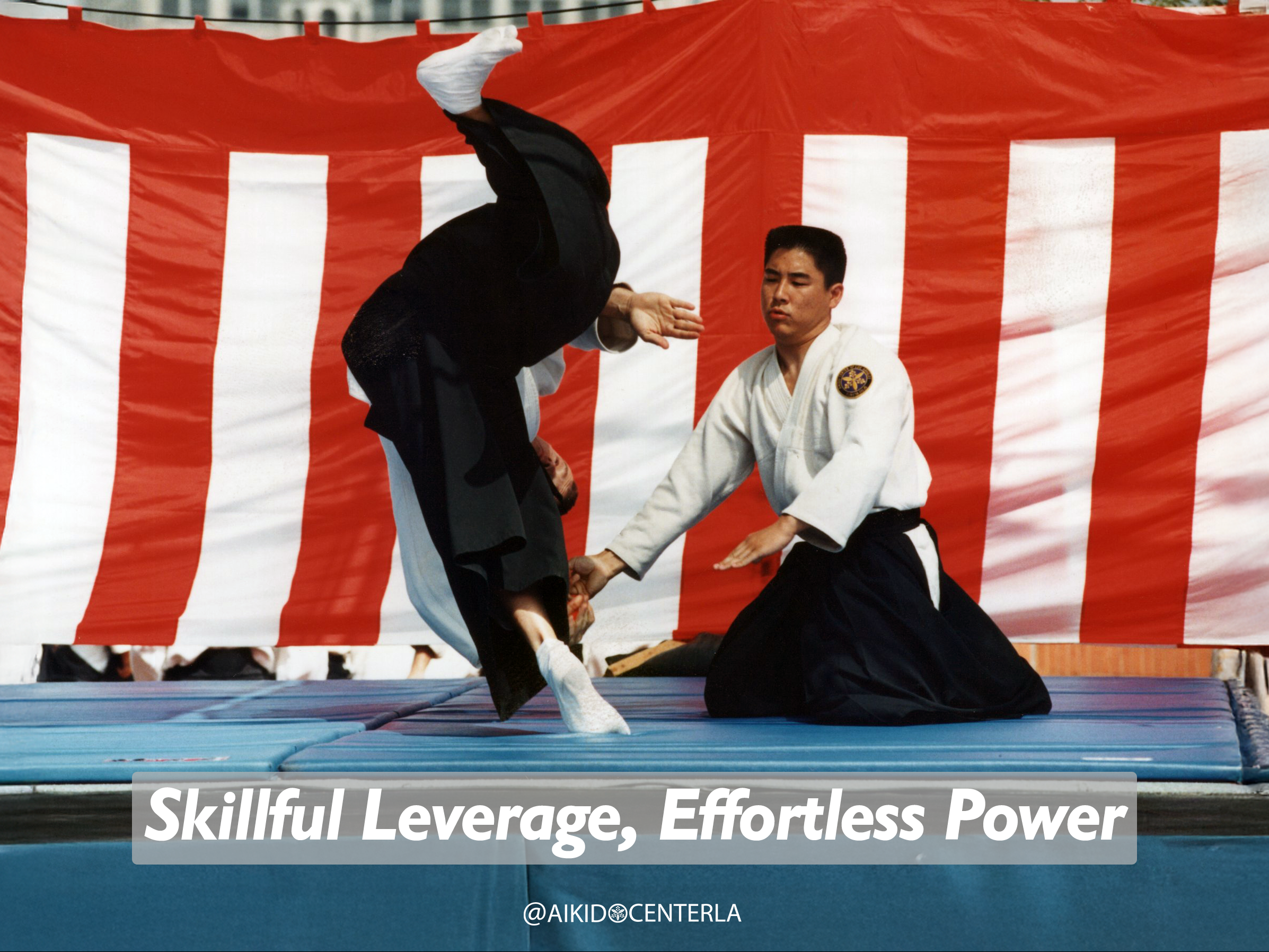

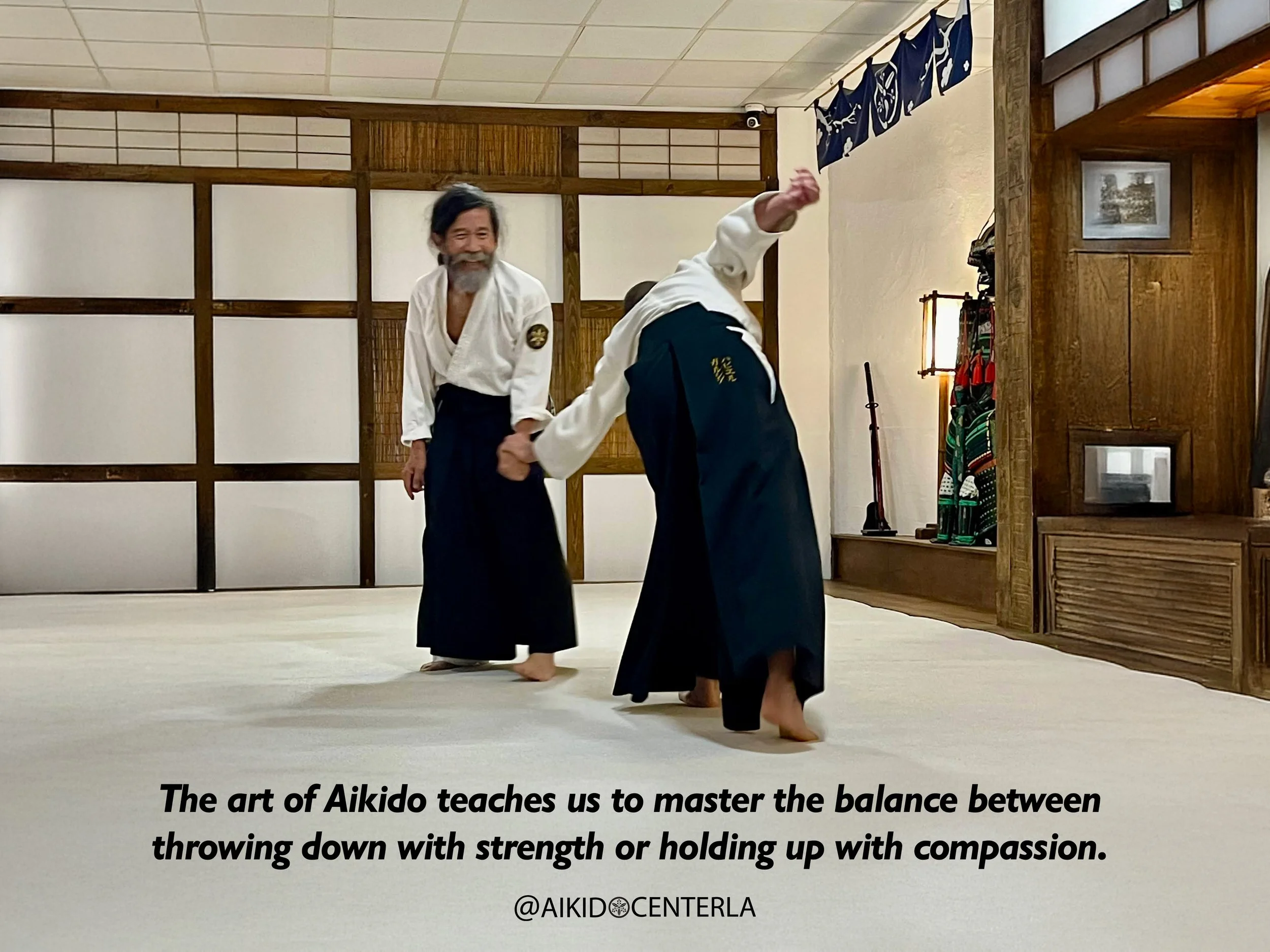

Regardless of what we call it, there is a brief moment within the movement of the technique right before the tug of the pull or the load of the push where the person’s balance is broken and they become light or are seemingly floating. It is at this point that we transform that unbalanced state into a technique and throw them down.

In this state of lightness or floating, what is really happening at this split second is that there is no resistance. The uke is not resisting the flow of the nage’s movement and the nage is allowing or not resisting the uke’s attack.

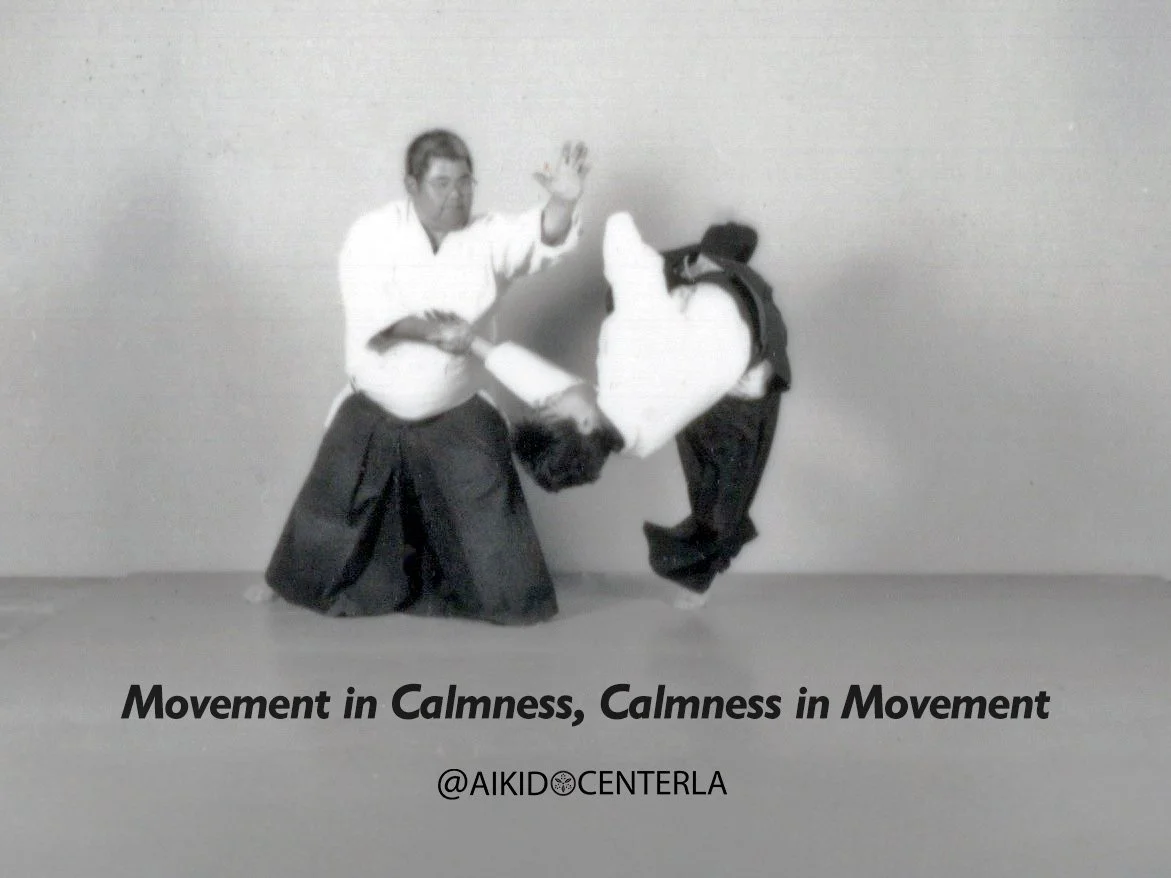

In training, the uke is supposed to resist by giving their partner a strong attack. However, in doing so, they expose themselves. So, they have to know at what point to abandon their initial attack to save themselves. Typically, this is the point where they move from attacking into a roll. If they hold on too long, they run the risk of hitting the ground with some vulnerable part of their body and getting injured. If they give in too early, it becomes fake and the nage never gets to feel what it’s really like to throw someone nor do they get to experience a strong attack. That’s why rolling out of the attack is a matter of timing rather than about intensity of attack. Therefore, we give as much resistance to help create growth, but not so much that it causes us to get injured.

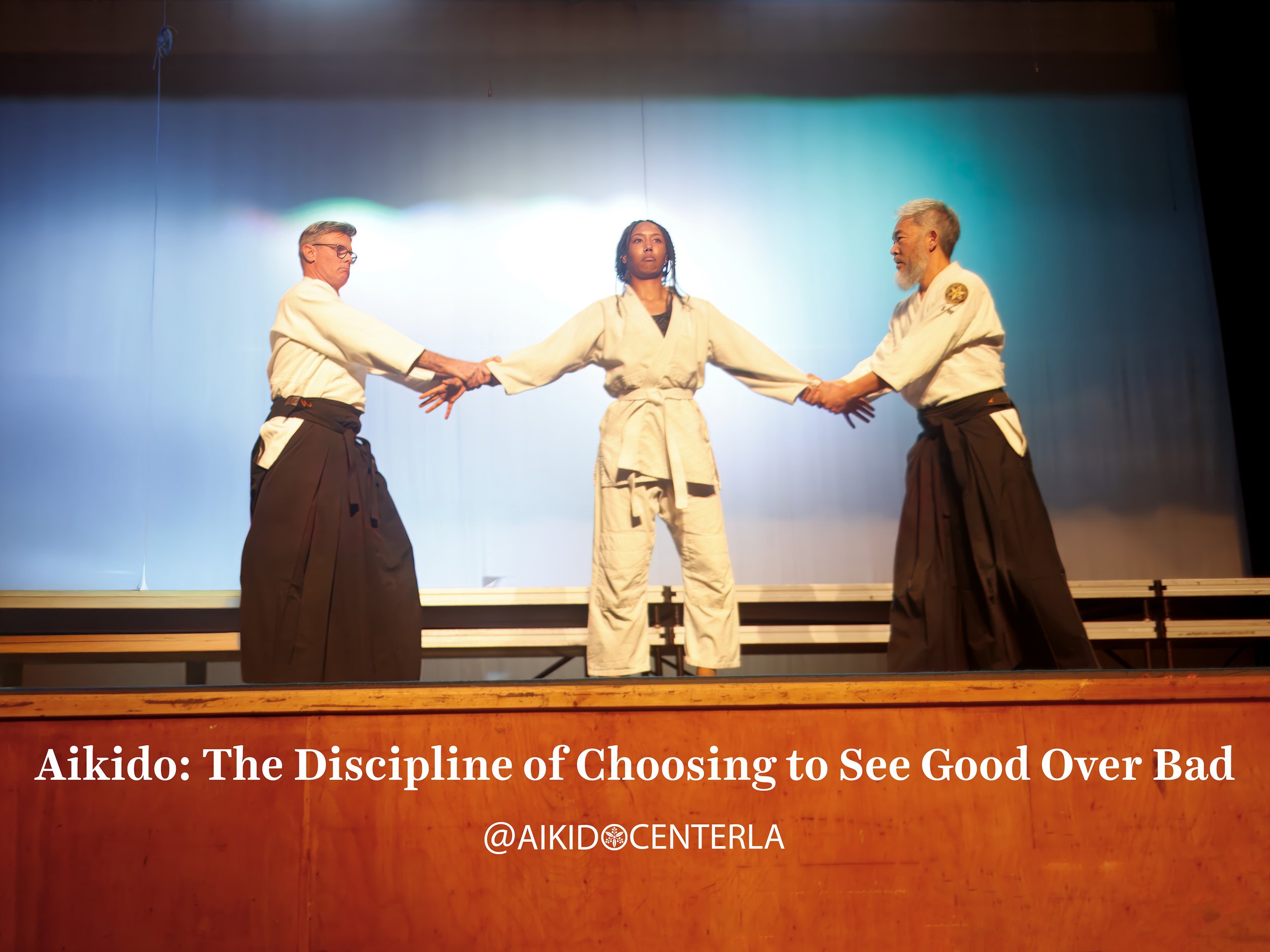

The problem becomes that some of us become so good at resisting that we don’t know when to stop and our resistance becomes pathological. In Aikido, we have to know when it’s time to resist and when it’s time to allow ourselves to be thrown. If we acquiesce too early, the nage never learns. If we submit too late, we risk injuring ourselves. Because we get good at resisting, we start to see that every problem becomes something to resist and resistance becomes a part of our personality. Training teaches us that not everything uncomfortable that happens to us is an attack. Most times the attack is merely the harbinger of change. Carl Jung once said, “We cannot change anything until we accept it. Condemnation does not liberate, it oppresses." Aikido is about learning how to go with the flow - we do not actively resist anything but only allow ourselves to accept it and transform it.

In Aikido and in Life, it is all about timing. There are times when we should actively resist and there are times when we should allow things to happen. The trick is in knowing one from the other. There is a great line in Max Ehrmann’s poem Desiderata: “You are a child of the universe, No less than the trees and the stars; You have a right to be here. And whether or not it is clear to you, No doubt the universe is unfolding as it should.” Life and Aikido unfold as they should and thus all we need to do is not resist and allow ourselves to go with the flow. That’s why the best Aikidoists know when to stop resisting.

Today’s goal: Think about what in your life you are actively resisting but should probably allow to unfold.

Watch this video to better understand Resistance