Students will always come and go, it's a fact of life, but what is really important is what they learn from us in the time that they are with us. A good teacher is then not judge by how good they are but by the lasting impression they make upon their students.

Gary Illiano sent me an interesting article written by Ted Gonder about the lessons that he has learned from his Aikido teacher, Donald Levine. I felt that each of his points were well thought out and poignant to anyone who follows the Way. They apply to not only Aikido, but to life as well.

How One Aikido Sensei Changed My Life (and 17 of His Life Lessons) By Ted Gonder

- Fall down, get up. Don believed in turning the fear of falling into the love of flying. He showed us that the floor was not something to be afraid of hitting or falling onto but instead just another surface, something to be explored and embraced. By learning to fall and rebound gracefully, with minimal friction or impact, toward your intended destination, we might live more freely. Whenever I came to Don for advice about failures and struggles, he’d smile and offer: “Fall down, get up!”

- Expect nothing, be ready for anything. In aikido, if you try to anticipate what your attacker is about to do, you open yourself up to danger because you’re living in the future rather than the present. The same is true in life: expectations open us up to danger. Any time we’re expecting one thing to happen and another does, we suffer: what are disappointment, anger, boredom, and frustration but unmet expectations? Don’s alternative was to instead remain “ready for anything”: centered, calm and alert at all times, armed with facts but aware of our limited perspective. By doing this we can avoid being surprised and always find the course of action leading to our desired results.

- Step off the line and witness your attacker. Have you ever watched an angry person while they’re on the attack? They’re completely out of control: their pain is so overwhelming that they can’t keep it inside anymore, so they spill it onto others. Normally when you’re attacked the natural response is to run away in fear or to fight back with reciprocal anger; in aikido the first step is always to step out of the way of the attack so that you can witness your attacker. Don showed us how while witnessing our attacker, we might muster compassion and pity for this suffering, angry person. This sense of pity allows us to move past being a victim to responding with what Marcus Aurelius called “kindness and justice.”

- Act from your center. The Eastern arts make a big deal about “the center” — a point below the belly button where all your energy comes from. Don took aikido’s practice of “getting centered” and extended it to real life situations: speeches, important conversations, negotiations. The idea is to gather yourself before acting: to relax, fix your posture, take a breath, clear your mind, ask yourself what matters most, what you value, who you’re fighting for, where you come from, where you are, where you’re headed, and how you feel. Can you imagine how the world might be different if more people took the time to “center,” or how your life might be different if you would?

- Learn the technique to forget the technique. To get good at aikido, you have to practice the techniques so much that they become automatic, reflex. But technical proficiency doesn’t make a great aikidoist. Great aikido comes from the the transcendence of technique: to move freely and masterfully, one must forget what’s been learned. Don would repeat aikido’s founder: “Any movement, intact, can become an Aikido technique, so in ultimate terms, there are no mistakes. My advice to you: Learn and forget! Learn and forget! Make the techniques part of your being!” This principle extends to every pursuit worth mastering — music, business, chess, parenting — learn the discipline so that you can break free of it.

- The most important practice happens off the mat. In any discipline requiring sacred space and regular practice — yoga, meditation, aikido, temple, church — the most important thing is not that you go to your Bikram class to get your fix or go to church to feel like a “good Christian” for that Sunday, but that you carry out the principles of that practice out in daily life: the real dojo. Practice “on the mat” is only to strengthen your foundation of technique and philosophy, to recenter so that you’re more capable of living out that practice “off the mat.” That’s the point of aikido or yoga or any other discipline. It’s not to get fit, or sweat a little, or check the box so you can tell your friends; it’s to become a better human being.

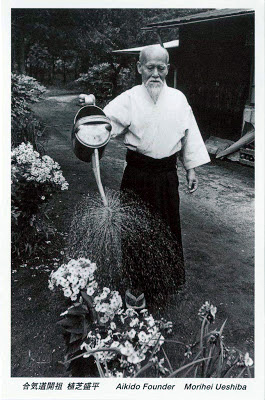

- Everything is training, training is process, and process is beauty. For a while, I served as Don’s personal assistant on business matters: I’d take dictation from him on emails, run errands, clean his house, water his plants, landscape his yard. Some things — like helping write important emails to influential martial artists or political figures — I found thrilling. But a lot of what he had me do bored me to tears, especially menial tasks such as cleaning and gardening. And it showed: I’d convince myself I was done weeding his garden and he’d come out and be like “Seriously, man? You missed like a thousand spots. It’d better be done the right way when I come back in a few hours.” After several instances like that, I still wasn’t getting the message. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t seem to muster enough enthusiasm to complete these tasks to perfection. Then one day, I attended an aikido practice in Don’s backyard, where we swung our wooden swords (boken) thousands of times in a row until our shoulders burned with lactic acid and my mind burned with boredom. After about a thousand swings, something happened: the swinging of the sword became automatic, my shoulder pain faded into the background, and I started noticing my breath, the breeze, the angle of the sun on the flowers, and the beat of my heart. I started having random epiphanies about projects and relationships. And suddenly I wanted to keep swinging the dreadful sword — extreme boredom opened a door to brief and humble enlightenment. After the session, I told Don what I’d experienced and he related the sword-swinging to menial repetitive tasks: “they’re the same. Everything is training.” He explained to me that if I could get lost in boredom-inspiring processes, I could experience more moments like this, moments where the noise of the world fades into the background and the beauty of the present moment emerges. Don taught me to fall in love with these repetitive menial tasks, to do the work. Now I love doing laundry, taking out the trash, drying dishes — it’s some of my best reflective time, it’s when my best ideas happen, and it helps me cleanse my soul and rid myself of restlessness. The same goes for driving, sitting on public transit, and waiting in line — these are meditation opportunities, not dead time. Chances to practice patience, to observe beauty.

- Defy the instinct to look for differences, and instead seek out common ground. We as humans at the cellular level are the exact same. It’s only because of our flawed perception and personal insecurities that we seek to name one another’s differences: black, white, man, woman, tall, short, conservative, liberal. We myopically construct identity based on false perceptions, superficialities, and assumptions, so that we can form tribal alliances to survive. In reality, all this effort to identify distinctions between us only leads to that which aikido warns against: that we see each other as adversaries rather than as partners. Don had faith in humanity as a whole, saw through false labels and their consequences, and encouraged human unity. His actions spoke for themselves, and inspire me every day to look beyond what divides us toward what unites us.

- Embrace the gray. Don believed that nothing in life was so simple as to be “black and white.” He believed the worthiest task was to navigate “the gray.” I’d sometimes share with Don my insecurities about the fact that I didn’t self-identify as a democrat or a republican, or that I didn’t have strong opinions on hot-button issues such as foreign policy (should we intervene or self-isolate?) and the macroeconomy (should taxes be high or low?). I feared that my lack of opinion might lead me to be an unengaged citizen in a time when too many citizens sit apathetically by the sidelines. Don offered comforting perspective by telling me what matters is my ability to navigate the gray and not just listen to the shrill divisive voices at the extremes. He showed me that often even more important than taking a particular side is helping people to understand that an issue might be more complex than it’s made out to be by “experts” and popular media. He pointed me to a Martin Luther King Jr. quote that has guided my thinking since: “The strong man holds in a living blend strongly marked opposites. The idealists are usually not realistic, and the realists are not usually idealistic. The militant are not generally known to be passive, nor the passive to be militant. Seldom are the humble self-assertive, or the self-assertive humble. But life at its best is a creative synthesis of opposites in fruitful harmony. The philosopher Hegel said that truth is found neither in the thesis nor the antithesis, but in the emergent synthesis which reconciles the two.”

- It’s okay to cry. In fact, it’s manly. Coming from competitive sports and fraternity life, I’d been programmed to think that crying was a sign of weakness in men. Like many guys, I’d conditioned myself to “plug up” emotion. For as rare as it was for me to shed tears, it was rarer for me to see another man cry. So it took me by surprise when one night over Scotch, Don began crying. While sharing about his experiences in Ethiopia during the revolution, he opened up to me about the death of one of his friends, and he cried tears of sorrow. In that moment he showed real grief, sadness, and character, and in the moments and days after I couldn’t help but think of how powerful those tears were, and how stupid it is that crying is thought of as unmanly. A couple of years later, during a tumultuous time in my work, Don reached out to me to meet — he said it was urgent. We met near his house and he told me with a look of genuine concern that he was worried about how many aikido practices I was missing at the last minute due to my unpredictable flight schedule. He weeped courageously: “I don’t want to lose you, man. You’re too damn good to lose. Get it together.” His vulnerability to weep openly showed me the truth behind his words: my behavior was hurting him, he deeply cared about our relationship, and he deeply cared about my development as his student and friend. His courage then set an example for me and showed me the way: a year later, when I told him that I’d be naming my newborn son after him, I couldn’t help but hold back my own tears.

- Attachment has power. For a while, I found it contradictory that Don was such an avid subscriber to the Asian traditions, yet decorated his house generously with artwork and other material possessions. After all, the Buddhists disbelieve in attachment to the material. So, eventually I raised the critique: “why do you have so much artwork? Why attach yourself to that? The Buddhists say that attachment is the cause of all unhappiness and suffering.” His response shut me up: “Without attachment, wouldn’t life be devoid of all meaning?” He helped me understand that even if detachment is what makes life livable, attachment is what makes life worth living.

- The mind can travel by plane, but the heart travels by foot. Don spoke English, Amharic, French, German, and a little Spanish, Italian, and Japanese. When he was 16, he was involved in the formation of the youth United Nations — just as the real United Nations was forming. As a young Jewish college student, he went to Germany study abroad — right after WWII. Early in his career, he journeyed to Ethiopia from Chicago to New York City to Paris then along the entire African coastline by ship. He understood travel. And once as we were on a flight from Chicago to Frankfurt together before venturing through Germany for an aikido seminar, he told me “the mind can travel by plane, but the heart travels by foot.” If you want to get to know a place as you’re traveling through, recognize the intangible trade-off you make in exchange for speed. Walking and jogging put you in touch with the people and the sidewalks and the pedestrian life of a place. Bicycles, too. Buses and trains allow you to sit into a place as you pass through it, and give you the window to peer out of and watch, to ponder as you enter that space between this town and the next one. These all let your heart beat in sync with your locale. But planes don’t: planes pick you up in one place and drop you in another, more quickly than is natural — you miss the life on the way and need to settle in for days or weeks before truly syncing with the new location. Planes are good if you need to conduct a transaction, and get somewhere very far or very fast, but not if you want to “be” there.

- Be an advocate. Don wanted his students to become better human beings as a result of their educational experience. He was an advocate for his students, on a mission to help each of us develop a voice of our own that we could use nonviolently toward human progress as we ventured forth into the world. But Don was also an advocate for those who didn’t have a voice at all. He was always working on asylum cases as an expert witness for Ethiopian refugees, people who barely spoke English or whose families had been torn apart by war, or who were caught in a bind with unfair or misinterpreted law. This was some of his most fulfilling and meaningful work, and showed me that each of us can be an advocate.

- Be HOT. As much as Don was an academic and theorist, he was a deep believer in using his time on earth for the most pressing and interesting issues of the times. He encouraged me and others to live and work at the “Height of the Times,” to be “HOT:” to be aware of the world’s events, find relevant ways to contribute, and lead change on the edge, to ride the wave of history and contribute whatever you can to make it better than it would be without you. He took the phrase from Chapter 3 of Ortega y Gasset’s Revolt of the Masses which states “What, then, in a word is the ‘height of our times’? It is not the fullness of time, and yet it feels itself superior to all times past, and beyond all known fullness….strong…yet uncertain of its destiny; proud of its strength and at the same time fearing it.” For Don, being HOT meant helping guide major developments in the fields of social theory and Ethiopian scholarship, then helping make those practical through interdisciplinary teaching of a modern martial art. And he encouraged me not just to read the news or vote but to plug into the intelligence of my network and seek out the opportunities to truly lead change on the edge. I took his advice and ended up working on HOT issues through a Department of Homeland Security task force and on a Presidential Advisory Council.

- Vices make us human — lighten up. Don was perfect…at being himself. Which meant he had vices. One time early in our relationship I asked him how he was dealing with the pain of a leg injury, and he admitted to me that Scotch was his painkiller of choice. How surprised I was: here was this seemingly pure master of the spiritual arts, and he was boozing to deal with the pain!? This clashed with my image of him, but after I got past my initial feelings of naive judgment, I felt drawn toward him morefor this minor vice. It made him human. Another time, he invited me to grab morning coffee together just days after he’d been diagnosed with a dangerous illness. We met at a French cafe, and I was expecting him to order something spartan like mint tea and healthy fruit; instead he got a coffee with extra cream, and a giant morning bun. At the time, I was trying to develop discipline in my own diet, and seeing my mentor eat something unhealthy made me feel conflicted about my efforts. He invited me to share in feasting on the delicious morning bun; reluctantly, I accepted his offer. As I chewed the first bites, I barely noticed its amazing taste because I felt so guilty for breaking my healthy diet, but quickly I lightened up and let go. We shared the pastry, and ate many more in the months and years after. The morning bun became a shared vice. I never ate pastries with anyone except Don, and he wasn’t a big pastry eater either, but that singular harmless vice bonded us. Had I judged him for his vices, I’d have created unnecessary separation in what would become a very close bond; instead, by embracing his vices I was able to see him as a whole human, and open space for a deeper connection.

- Extend roots into the earth, and reach up toward the heavens. In aikido there are techniques that call upon “heaven and earth” — you disrupt your opponent’s balance by leading their attention upward and downward simultaneously: you render them top-heavy while setting their body into motion toward the floor. Don was exceptional at teaching us the value of these techniques on the mat, but even more so in life. To act from a centered place, one must be grounded, stable, humble. For this, we have to extend our roots into the ground and feel how our feet connect to the foundation upon which we stand. Don would have us take off our shoes and stand in the grass with our eyes closed, imagining that our legs had strong roots extending deep into the earth. We’d then push each other to test balance, and find that we’d become nearly impossible to topple. But to be grounded in the earth beneath us without any extension toward the heavens above us is to risk getting stuck. As trees grow toward the sky, they blossom, grow more magnificent, and give to other creatures. Don would have us reach toward the sky with yoga poses and qi gong exercises, and we’d feel our lungs expand, our mental awareness sharpen, and our energy increase. The practice of extending roots into the earth and reaching up to the heavens applies to nearly everything in life, from business meetings (ground yourself in reality while pursuing ambitious goals) to parenting (setting strong values and consistent routines while encouraging your kids to dream big).

- Find amusement in the human comedy. Don took his work seriously but tried hard not to take himself too seriously. For as much as Don accomplished in his life, one might have thought he had all the reasons in the world to be a really “serious” guy. But he was quite the opposite. Constant falling on the aikido mat at the hands of his students helped him stay humble, always able to laugh at himself, to see himself from his own “mental balcony” and find amusement. The last words I heard from Don before he passed away were from an audio recording he sent out to a group of friends, in which he said “I continue to be amused by the human comedy.” Until the very end, Don was able to see the world clearly, and even in all his pain, crack a smile and see the humor in it all.

Source: http://observer.com/2016/01/how-one-aikido-sensei-changed-my-life-and-17-of-his-life-lessons/