"Knowing your own darkness is the best method for dealing with the darknesses of other people.” - Psychiatrist Carl Jung

Many cultures believe eclipses are omens of doom. To Japanese marital artists, an eclipse can be thought of as the harbinger of the martial arts.

The Chinese god Zhang Xian is often depicted aiming an arrow at a dog named tiangou who is trying to eat the moon. As a good spirit, tiangou brings peace, tranquility, and gives protection. As an evil spirit it eats the moon causing an eclipse. The word tiangou translates into Japanese as tengu (天狗). In Japanese folklore, the tengu are supernatural beings who are thought to be knowledgeable in the martial arts and taught people those arts.

There is a famous Noh play called Kurama-tengu which tells the story of Minamoto no Yoshitsune. The play begins with monks and children from the Kurama temple enjoying a cherry blossom viewing. The group leaves in protest when a shabby Yamabushi or “mountain ascetic priest” arrives and tries to join them. Only one child stays and confides in the Yamabushi that he is Minamoto no Yoshitsune or the orphaned son of the slain head of the Genji clan. In turn, the Yamabushi reveals himself to be the head tengu and proceeds to instruct Yoshitsune in the martial arts. The play closes with Yoshitsune avenging his father's death using the skills he learned from the tengu. Interestingly, Yoshitsune is the distant nephew of Minamoto no Yoshimitsu who is more commonly known as Shinra Saburo and is the creator of Daito-ryu Aikijujitsu or the parent form of Aikido.

Ancient civilizations believed that eclipses were bad omens but actually what they feared was the unexpected. This is not without merit as all warfare is based upon deception and the element of surprise is its ultimate fighting technique. Therefore, it is only natural that we should be weary of the unknown and the darkness that eclipses bring.

Aikido is supposed to be a higher form of the martial arts. Our goal is not to destroy - it is to know. In route to knowing who we are, Aikido training teaches us to believe in ourselves. With each opponent and adversity that we overcome; we grow stronger. We grow stronger not in the skill of defeating others but in the skill in believing in ourselves. Psychiatrist Carl Jung said, "Knowing your own darkness is the best method for dealing with the darknesses of other people.” If Jung’s assertion is true, then we only become truly undefeatable when we know who we are and believe in ourselves.

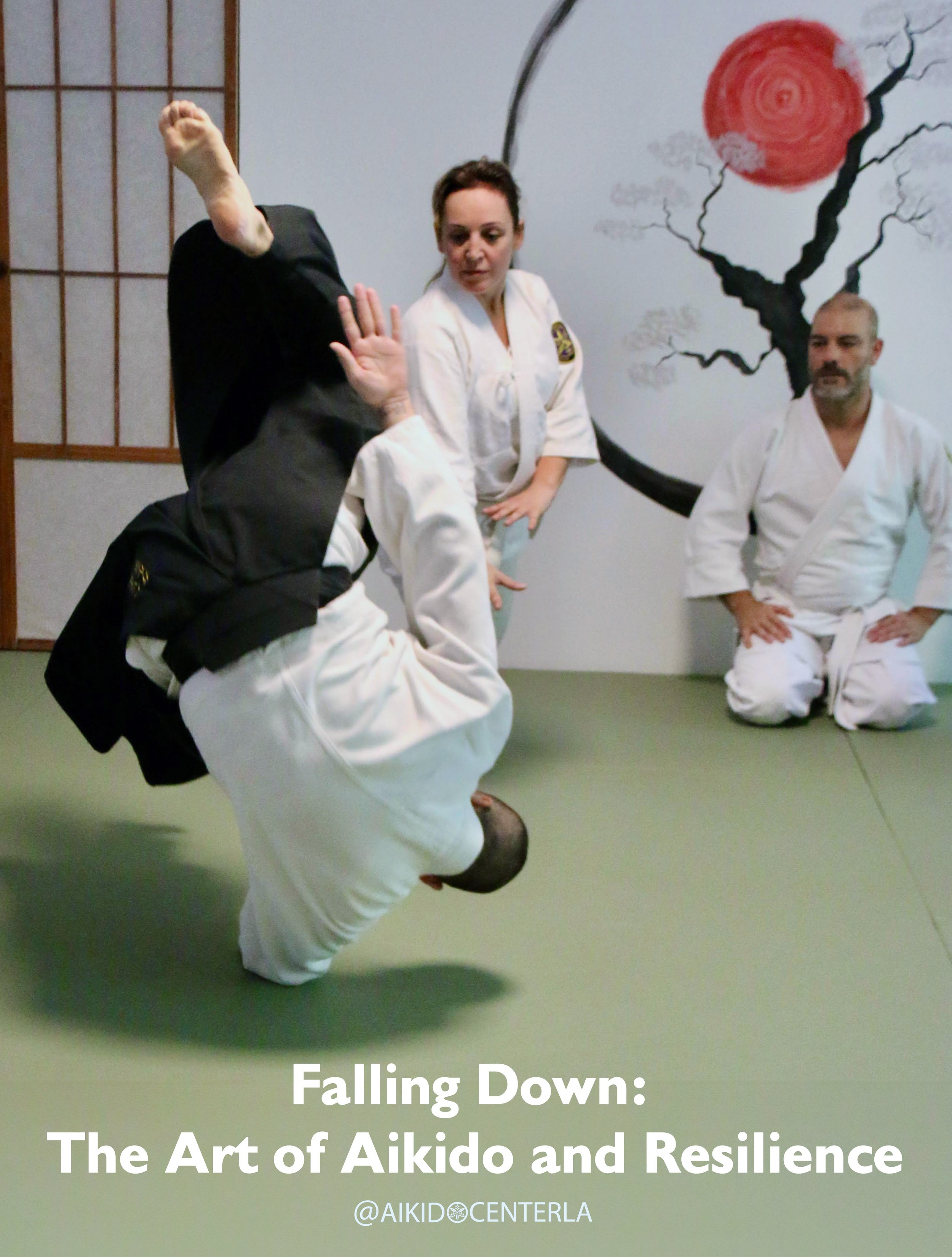

Don’t be afraid of the eclipse. Its darkness can bring us the true power of the martial arts - knowing ourselves. Aikidoists do not fear what they do not know. Instead, they believe in who they are and the person that they have trained to become. Greek philosopher Archilochus said, “We don't rise to the level of our expectations; we fall to the level of our training.” The best Aikidoists don’t cower in the darkness, they excel in it.

Today’s goal: Don’t be afraid of the eclipse and its darkness, just be careful looking directly at it.

Watch this video of Gabor Mate talking about the darkness