When the teacher is the greatest adversary of the student

In the past, it was thought that the best teachers were the ones that were the most unreasonable. Regardless if the teacher was “good” or not, being unreasonable forces the student to have to work harder. This is why, in olden times, teachers prided themselves on being shakushijougi (杓子定規) or “strict.” In Japan, it is thought that students have iji (意地) or “obstinance” and that without training that willful spirit would cause them to be unsuccessful. Thus, it was the teacher’s duty to transform that willfulness into konjo (根性) or “fighting spirit” so that they could be successful. Therefore, in order to transform the student the teacher needed to be strict with their standards and unreasonable in their expectations.

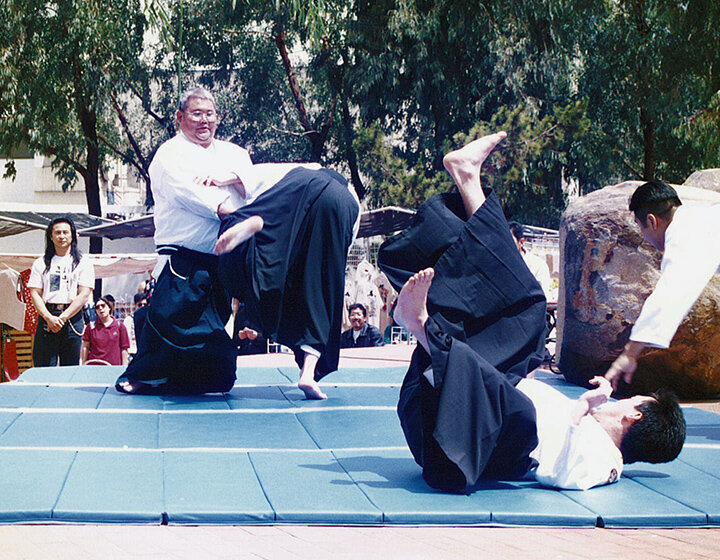

My teacher was Rev. Kensho Furuya Sensei who attained the rank of 6th Dan in Aikido and a 6th Dan Kiyoshi in Muso Shinden Ryu Iaido. When Furuya Sensei passed, he had been studying martial arts for over 50 years. Furuya Sensei was a Zen priest, scholar and traditional Aikido and Iaido teacher who valued and embodied the old ways of budo.

When I was a student, one summer I started washing Furuya Sensei’s car in exchange for monthly dues. Every Saturday after class, I would wash and wax his car in the alley in front of the dojo. Despite having washed his car a dozen times, he never commented on whether or not I was doing a good job. I was fine with that because just about every time I spoke with Furuya Sensei, he rebuked me about something like my haircut or my choice of t-shirt logo. Washing his car in the summer was great. I saved $100 dollars a month and it only took me an hour. Then winter rolled in and that was painful. I am not sure how many days the weather was bad, but there was one fateful day that I remember which taught me a great lesson.

I came to the dojo on a Saturday as usual and took all the classes but this particular Saturday it was raining very hard. I remembered thinking, “Yes, I have the day off.” As I walked down the stairs, Furuya Sensei was sitting at the bottom talking with students as they left the dojo. I remember that I was happy and had a bit of skip in my step. I said, “Bye Sensei, see you tomorrow” as I walked out the door. All I heard was “No, no, no. Don’t you have a job to do?” I froze standing there waiting for him to laugh. But he didn’t laugh and everyone else stood their frozen witnessing my demise. Furuya Sensei said, “Aren’t you supposed to wash my car?” In that moment, you could have heard a pin drop. I said, “But, Sensei, it’s raining outside.” He said with a stern look, “A deal is a deal.”

As I began to wash Furuya Sensei’s car in the pouring rain, he and one of the students left for lunch. As they drove away, there was a bolt of lightning which to me seemed like an ominous sign because at that moment I was thinking about cheating and not washing his car and just saying I did. For what seemed like forever, I waffled back and forth as to what to do. All I could think about was that he was testing me and watching me from one of the restaurants or apartments around the dojo. I thought that it might be a test and that he was trying to catch me cheating.

So I decided that since I was already drenched that I would just wash his car as usual. I must have looked like a crazy person as I stood in the rain washing a car only wearing a throughly soaked t-shirt. Just as I finished waxing Sensei’s car (yes washed and waxed was the deal), he pulled up, didn’t say a word and hurriedly went inside the dojo covering his head from the rain. Someone else waited at the door until I was done to get Furuya Sensei’s keys and put away all the equipment. Tired and soaking wet, I got into my car and went home.

Furuya Sensei never said a word about that day to me, but I learned a great lesson - a deal is a deal. In Japanese, they say, “Bushi no ichigon kintetsu no gotoshi" which roughly means that “A warrior's word is gold.” If I say that I am a martial artists then I must act like martial artist.

A month or so later, I could afford dues again and so I didn’t have to wash Furuya Sensei’s car anymore. I still did it sporadically for many years after, but never again in the rain.

In the old days, the teacher what supposed to be the student’s greatest adversary. The teacher’s harsh treatment was supposed to light a fire inside of the student so that they would do whatever it took to defeat them. The teacher was not supposed to be a friend. If the teacher was friendly to you then it was thought that they weren’t interested in developing you. That was because in order to create change in the student, the teacher was going to have to be willing to hurt the student’s feelings as they pushed them out of their comfort zone. When talking about this, Furuya Sensei would often say, “In order to make an omelet, you are going to have to break some eggs.” Teachers in the olden days were preparing students for war and the rigors of battle. That immediacy necessitated that the teacher be harsh and almost unfair or in other words unreasonable.

I studied with Furuya Sensei for 17 years and one day. That one day extra day after 17 years was the true test of all of his teachings. It was the final exam. Did his unreasonableness make me or break me? Did his teachings sink in and put me on the right path? Would I do whatever it would take to keep the dojo open? Only time will tell. Only now after 15 years since Furuya Sensei’s passing do I realize what a gift he gave me when he made me wash his car in the rain. By being unreasonable, Furuya Sensei forced me to make a decision about who I was going to be - a warrior or cheater. When we say we will do something or say that we are someone, then we have to live up to those words. Now today, decades later I understand. Many times throughout my training, he taught me some hard lessons with his unreasonableness. I can say without a doubt that without Furuya Sensei’s unreasonableness I would not have become the person that I am today.